Narco Refugees

The Vasquez family is on the run. It is not from the endemic poverty, lack of job opportunities, or deficits in government aid, which have historically driven Mexicans across the border. They are running from war.

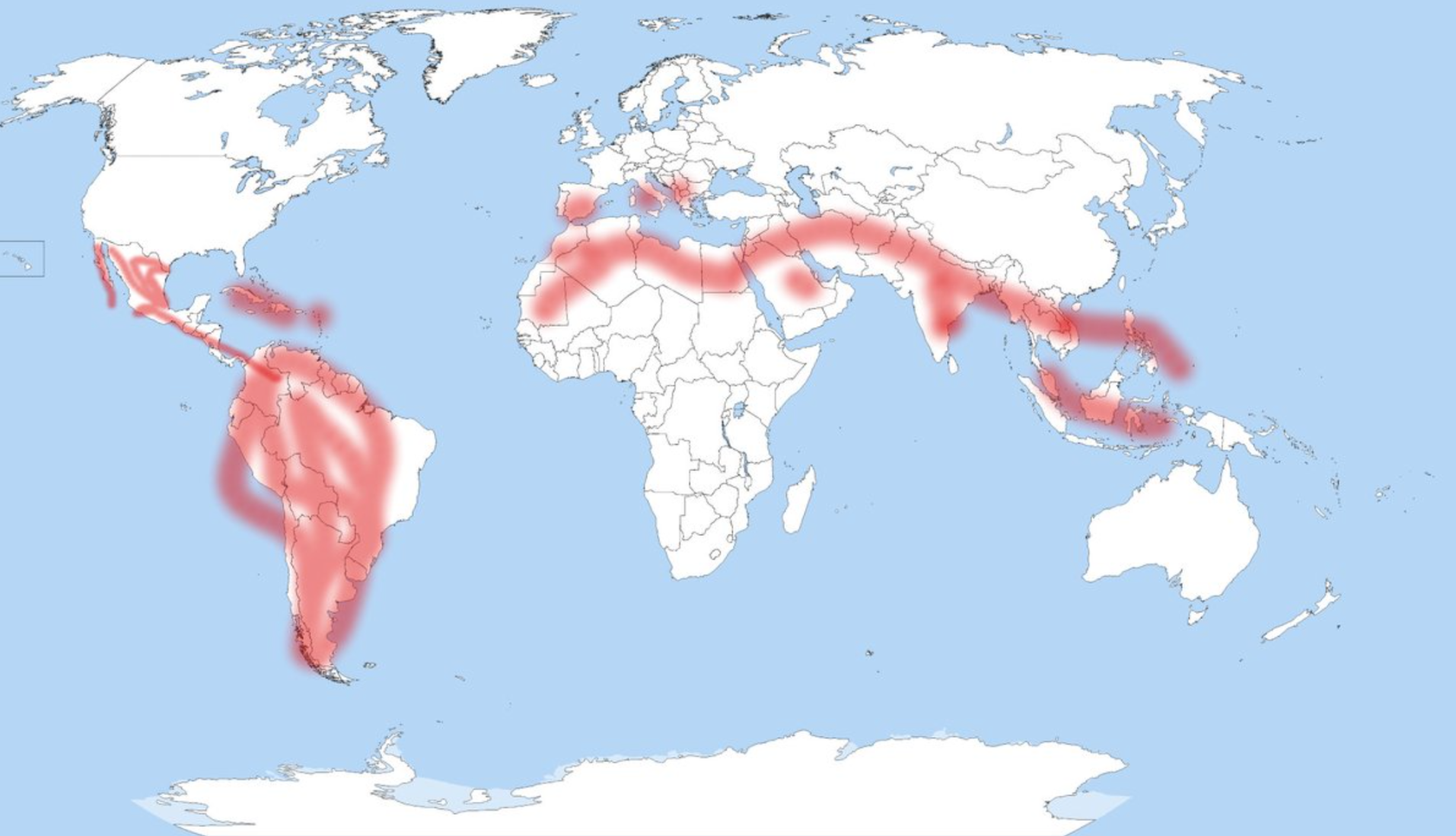

Mounting violence induced by Mexico’s drug war has displaced 230,000 Mexicans thus far, according to the Internal Displacement Monitoring Center.

After gaining political asylum and fleeing to the US, Jose Vasquez contacted my father who agreed to shelter him and his family who are my distant relatives.

I had begun to hear pieces of their harrowing story from various family members. They were shaken from their ordeal and understandably in no condition to disclose their story in an interview.

The Mexican drug war hardly crossed my mind before then. It only existed in the snippets of media stories I heard from time to time. Meeting Jose Vasquez and his family last month brought the reality of the drug war much closer to home.

Back in Mexico, the Vasquez family owned a small business and three cars. Jose Vasquez worked as a mechanic, while Maria Vasquez ran the local neighborhood grocery store. The children enjoyed comfortable lives.

They were living the “Mexican Dream,” but in an American graveyard. As the body count rose, their comfortable lives shattered, leaving behind shards of their once happy lives for the wind to scatter across the border.

Jose received a call from police asking him to identify a corpse, that of his brother Martin, which had been discovered at a crime scene. Martin had been involved in the drug trade, fueling speculation that cartel assassins murdered him.

According to the Guardian, the Mexican government has placed the death toll for drug-war related violence at just over 34,612. There seems to be no end in sight.

Martin was survived by his wife who had given birth sometime after his funeral. She was then under the care of Jose’s other brother Joel. Sometime after Martin’s wife had given birth, the assassins arrived and finished the job: murdering Joel, the young wife, and her newborn baby.

Drug trafficking and cartel warfare have shaped the destinies of Mexico’s “Ninis” generation, the wasted youth que “ni estudian, ni trabajan,” who neither study nor work, according to the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting. From the age of 11 years old, they make their living as sentries, traffickers, and hired guns for the warring cartels, as reported by International Business Times.

The rising tide of violence and corruption has even managed to pollute the dwindling reservoirs of justice and morality within the police force. According to the L.A. Times, 3,200 Mexican federal police officers have been investigated and fired for links to drug cartels.

Distraught over the massacre of his relatives, Jose yelled at the officer, asking him when the violence would end. The officer retorted that it would end when none of his family members were left. Profoundly aware of this rampant corruption, Jose promptly took his family to Tijuana to ask the American Embassy for political asylum.

In 2008, only 13 percent of Mexican political asylum requests were granted according to Paul R. Kan of the Strategic Studies Institute. Fortunately for Jose, the family was granted 6 months of asylum, time which he hopes to use to secure his family’s residency and safety.

After staying in my family’s home for a couple of days, the Vasquez family left for Chicago where they will have their residency hearing, and where they may finally begin rebuilding their lives.

How many images, how many sensations, how many unspoken horrors have resurfaced in their memories since then?

*The names mentioned herein, of the family and its individual members, have been changed in order to respect their privacy and maintain their safety.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!