Photographer George Rodriguez’s “Double Vision” Retrospective at The Lodge

Even before crossing over to The Lodge at 1024 N. Western Ave., the crowd was visible. As young Latinxs, my colleague Maria Amaya and I were both nervous yet ecstatic to meet the highly-esteemed Latinx attending George Rodriguez’s Double Vision retrospective at The Lodge. Entering the space made it clear that we were more than welcome to join the dozens of conversations between artists and activists that continued into the late evening. The three sections of the gallery space allowed us to view the works in two rooms and mingle on the outdoor patio. The space catered well to the exhibition and led to a success in representing the two worlds in which Rodriguez participated: one of fame and the other of activism.

Maria Elena Chavez, standing next to a portrait of her uncle Cesar E. Chavez by George Rodriguez (1969). Image Credit: Israel Cedillo

It’s always a pleasure to meet impactful and driven people from the Chicanx community because of their welcoming attitude and inspiring work. Maria Chavez, niece of Cesar Chavez, is one of those people. Having grown up in the forefront of the Chicanx movement she understands the critical need “to have our own supporters documenting,” as Rodriguez was doing. Yet, even it was a surprise to Chavez to learn that his photographs did not stop there; “he lived this double life and yet was so humble.”

Rodriguez’s humility furthered not only his own success but also the success of immigrant and minority groups. It’s his skill and character which is truly admirable. His method of portraiture makes it easy to compare his portraits of pop-icons such as in the pieces Marilyn Monroe (1962) and Cesar Chavez (1968); each of the subjects is portrayed with a great sense of pride and respect. The selected prints presented allowed the audience to see these worlds of celebrities and activists slipping into each other throughout the past couple decades, the hazy penumbra of celebrity and ideas flowing together personified by the lively crowd easily moving between the two separate rooms and ideas.

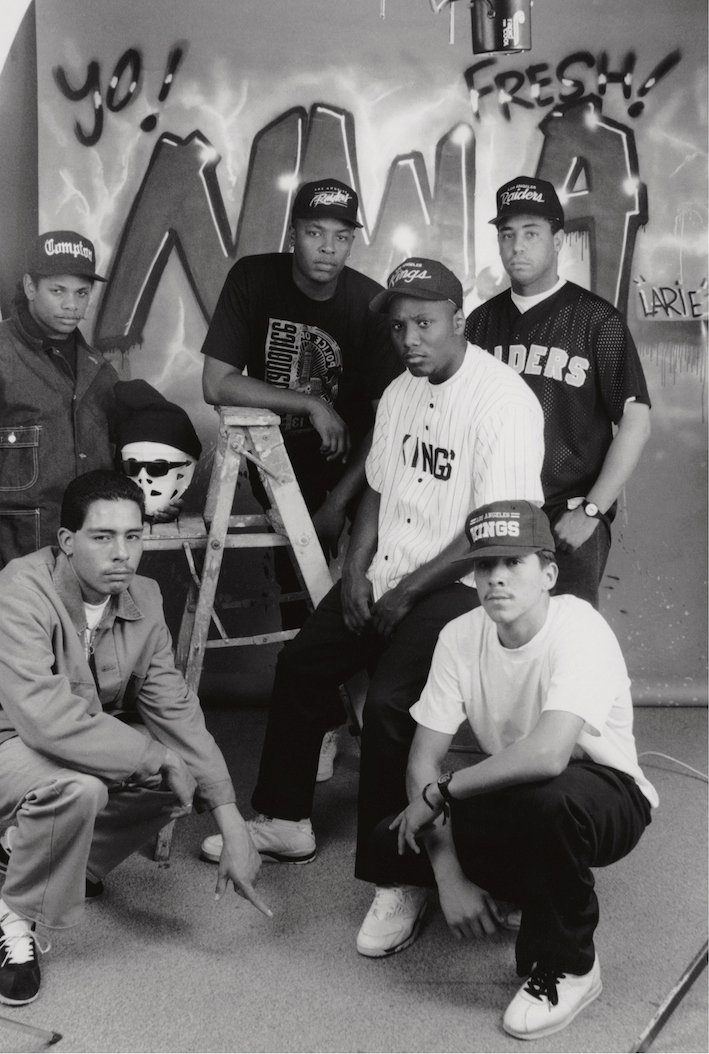

Three other images grabbed my attention; two of which focused on a main overarching theme of the exhibit, the hidden realities of black and brown communities. The N.W.A. diptych N.W.A., & N.W.A., Keen, and Larie Ruelas (1990) shows that although controversial and villainized, the unity of Latinx and Black folks is a force to be reckoned with, and to be admired. It is this cohesive network(ing) between graffiti artists and rappers that allows for the work like that of NWA to come to fruition. East L.A. (1970) is a shift away from the typical perspective of a military member coming back home. The compositing of the soldier and the ghetto evoked a similar mood as when watching the exposition of 1932 film I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang. The story of a soldier’s return from WWI to the devastating state of America in the Great Depression of the 1930s contrasts with the struggle of the soldier of color coming back to his poverty-ridden ghetto. The still East L.A. holds the viewer onto this moment even tighter.

The third image, Hilary Rodham-Clinton (1980), connects the lenses of sociopolitical movements’ icons with that of individuals like Carmen Perez, community leader at the Centro de Niños. This moment captured not only her interaction with Clinton, but also the tender memory of her now deceased mother.

Perez looked at the framed photograph while reminiscing on this moment of her mother, “Right when it was taken [George] gave me a copy. This was a treasure for me especially because my mother is now in heaven, and no one can take away that memory.”

With our current political climate, Rodriguez’s work is as achingly relevant and dangerous as it was when he captured the images. The true question that our society must answer now is: will his work remain relevant for years to come? With this year’s Pacific Standard Time LA/LA exhibitions there was a rise of viewership for Latinx Art, and Rodriguez’s exhibition shows that this is not where our community’s voice ends. However, the most essential lesson this exhibition presents to us is not the content, but the process in which the artist works: He doesn’t believe that he was “taking a stance” himself instead, he demands to note that “as journalists we’re just recording and I only take the photos, I don’t dictate the policy.” He pushes this idea further by saying “people think it’s a movement; but people don’t understand the farmworkers see it as their own lives.”

As an artist, I respect this way of documenting and sharing moments and his ability to take a step back before taking ownership of someone else’s actions. It is simply too common these days for artists to make work without any research into the subjects they are representing; examples of this are Dana Schutz’s Open Casket (2016) piece for the Whitney Biennial and Sam Durant’s Scaffold (2012) which was to be installed at the Walker Art Gallery’s Sculpture Garden. Both of these works referenced the dead bodies of people of color without consideration of how as artists they were taking ownership and reshaping the context in which these bodies were interacted with. It is thanks to artists like Rodriguez that we can keep these problematic pieces in check.

Rodriguez’s retrospective at The Lodge will be up until July 14th. His book was also released with the opening of the show and can be purchased here (https://hatandbeard.com/products/double-vision-the-photography-of-george-rodriguez).

Hilary Rodham-Clinton, Los Angeles, 1980, 20.5” x 24.5” (Framed). Analog Silver Gelatin Print. At The Lodge on Western Ave. for George Rodriguez’s “Double Vision” Retrospective. Image Credit: George Rodriguez

N.W.A, Keen, and Larie Ruelas, Burbank, 1990, 24.5” x 20.5” (Framed). Analog Silver Gelatin Print. At The Lodge on Western Ave. for George Rodriguez’s “Double Vision” Retrospective. Image Credit: George Rodriguez

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!