The Curriculum That Distances Us

By: Angela Vargas

Photo by CSUF Photos via Flickr

Learning about our history is a choice many minority students make in our college careers. We take ethnic studies courses in hopes of gaining a better understanding of our identities. However, in a diverse country like the United States, why isn’t this mandated in the K-12 curriculum? Why must we have to seek it on our own?

Unfortunately, this is the case in a curriculum that lacks diversity.

Latinx students go through most of their childhood not seeing themselves in history books or academia. This is shocking considering there are 17.9 million Hispanic students in school, according to a study by the US Census. If enrollment is so high, why are most Latinx contributions excluded from the curriculum? Why aren’t the harsh realities of the U.S. treatment towards Latinx people included? It makes one wonder whether the American academic curriculum is constructed as a way to make young Latinx students assimilate to American culture by banefully excluding their histories.

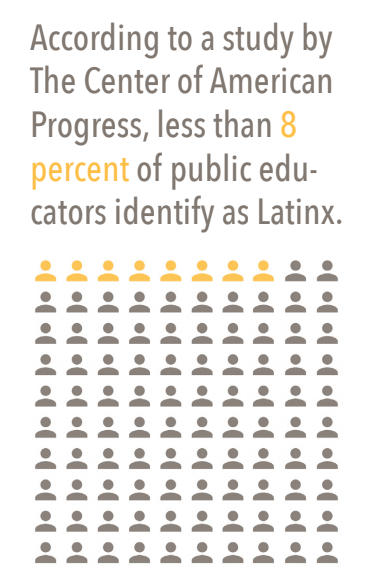

With high Latinx enrollment, there comes a need for representation among educators. Teacher diversity has yet to catch up with the growing number of Latinx students. According to a study by The Center of American Progress, less than 8 percent of public educators identify as Latinx. Navigating the American academic curriculum is made difficult when our histories aren’t accurately portrayed. It’s even harder with little-to-none Latinx educators that students can relate and look up to.

Most Latinx values are rooted in prioritizing family. Meanwhile, American values are rooted in individualism. This becomes complicated for Latinx students when navigating their college careers. White teachers would encourage Latinx students to follow their dreams, even if it meant moving away from home; this goes against the ideas Latinx students hear at home about supporting their families. This isn’t to say that the advice to follow their dreams is wrong, but simply that it lacks an understanding of the values that Latinx students hold close. Having a diverse set of teachers helps students’ ideas of self-perception through the ways they can relate to them.

Illustration by: Mariana Orozco-Berber

Beyond those who teach us, representation lacks in the curriculum. In the Californian Social Studies standards for K-12 education, Latinx people are not mentioned until the fourth grade when discussing the Mexican-American War. They aren’t mentioned again until students reach seventh grade, when they learn about indigenous communities in the Americas.

These education standards are an example of how Latinx histories are constantly suppressed. It begins in kindergarten when students learn about Christopher Columbus. Then when students are taught about “California’s growing economy”, the Gold Rush, Texas Rangers, etc. All being suppressed histories, there’s no mention of the violent genocide, mistreatment of farmworkers, lynchings, and terrorization of Latinx people. If history courses choose to exclude stories of Latinx people, so will other disciplines.

“I would love to see the natural and physical sciences deal with the concept of race and racism.”

Daniel Solorzano, professor of Chicano/a and Central American Studies & Education

Latinx students aren’t allowed to discover their identities through K-12 academia. It’s not possible when we are taught as Americans. For example, It’s confusing for a young Mexican-American student to learn that we won the Mexican-American War. Who’s “we”? Being taught as Americans in school but Latinx at home creates an odd dynamic with identity. Forcing students to break up their identities into two different spaces or in some cases, completely suppress one of them.

When discussing our introduction to multi-ethnic literature, Professor of education at UCLA, Daniel Solorzano and I found that not much has changed since he was a student. We both sought literature outside of what the curriculum considered “classic” on our own. Reading literature from our backgrounds helped both of us understand our identity. However, literature is not the only discipline lacking in diverse voices. Solorzano argues, “I would love to see the natural and physical sciences deal with the concept of race and racism.” Often, the sciences seem to not be expected to increase diversity from their specified curriculums. However, representation is a multi-disciplinary issue.

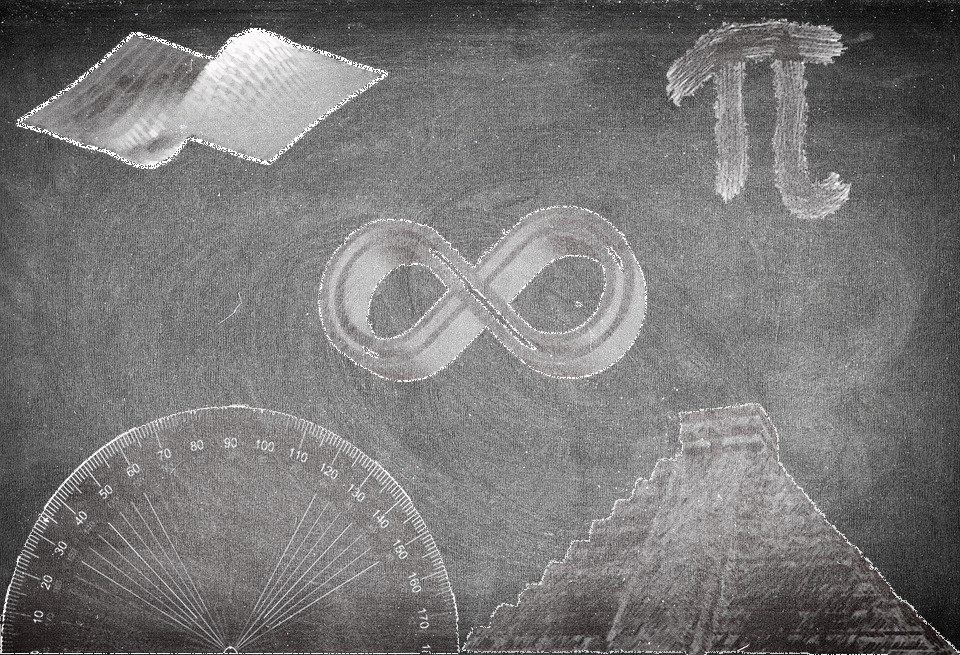

The introduction of AB 2772 Ethnic Studies in California is one step towards the right direction. Requiring ethnic studies as a means to graduate high school is a way to ensure a holistic curriculum. This curriculum helps keep up with the growing diversity in the student population. However, this isn’t a complete fix. Professor Solorzano fears that ethnic studies may lead teachers to believe that they are off the hook from diversifying their curriculums since ethnic studies will now have its own place. There is still a need to increase diversity in history, math, literature, and the sciences, regardless if ethnic studies courses are in place.

Overall, the K-12 education system lacks representation for a growing number of Latinx students. Reflections of ourselves go beyond textbooks: it’s in those who teach us, it’s in the curriculum that guides us. Students from diverse backgrounds must be able to navigate their identities in and out of the classroom.

Photo by Ernesto Aquino via Flickr

Latinx identity isn’t kept alive in dusty, outdated history books.

Latinx identity hung on by a thread;

through parents’ stories of migration and struggle.

Latinx identity prepared by recipes;

through helping mothers make the masa for tortillas de harina,

and feeling the heat of the comal on our fingertips.

Latinx identity suppressed by film;

through the way güeritas were praised,

and our Latinx features became exotic.

Latinx identity reincarnated by Chicano 10A;

through relearned histories and renewed pride,

of trailblazers who set the path for us.

Latinx identity is kept alive by those who demand to be heard.