Implications of Weaponizing the Immigrant Story

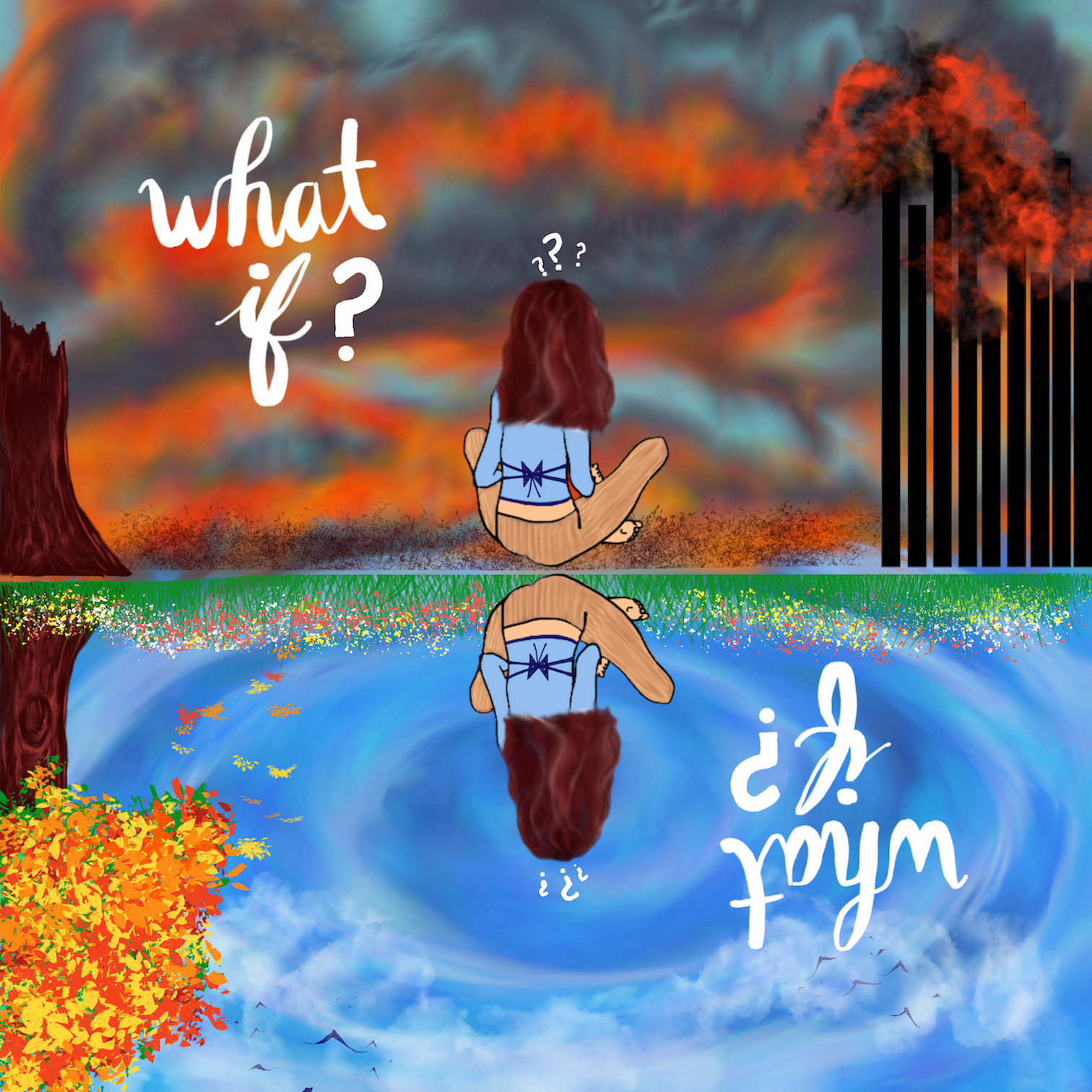

Visual by: Tommy Correa

“Weaponized incompetence” is the act of pretending not to know how to do something in order to waive out of a responsibility, thus placing it upon another person to do it. As Hanna Ngo, a first generation Vietnamese-American, says in a TikTok, it is a harsh reality for many first generation individuals. In light of this information, this strategic incompetence is also central in the Latine community. As defined by Esther Calzada’s article Incorporating the Cultural Value of Respecto Into a Framework of Latino Parenting, respecto, or respect in English, is the shared belief at the center of the social implications of this behavioral phenomenon, rooted in the dynamics between immigrant parents and their children at large (2010).

Ngo shares that she was surprised that her parents “forgot how to do any basic task and problem solving,” which has led to them summoning her any time they want help (Ngo, 2023). Ngo acknowledges the slight validity in her parents’ explanation for preferring for her to do their tasks for them, as her “English is better” because she “was born in the States” (Ngo, 2023). However, she questions their actual motives, considering how it could be possible that her parents could not read “the mail for the last five years before [she] moved back home” (Ngo, 2023). Claiming helplessness as a means to force others to lend a hand, instead of asking directly for assistance, is not an experience that is exclusive to Ngo, and it has caused a polarizing dialogue on digital platforms.

A vast majority of the controversy surrounding Ngo’s social media post is one that Ngo herself also recognizes: where do our parents’ sacrifices for us to be here begin and end? Although she recognizes her indebtedness, does this justify her parents strategically using their immigrant status in order for their daughter to do some or all tasks for them? Many Hispanic and Latine children are not strangers to this notion as “respecto emphasizes obedience and dictates that children should be highly considerate of adults…”, begging the question if that same consideration is returned (Calzada, 2010). This dynamic of wanting this mutual respect illuminates the integration of Western ideal of individualism; autonomy is one that often clashes with the obedience immigrant parents have raised their children with as an effort to conserve their culture. Being raised by contradictory ideologies causes these misunderstandings where the child is now questioning the expectations and seeking independence. A conglomerate of viewers from varying ethnic backgrounds provide their own opinions on social media, adding to the conversation that has transcended racial barriers. Many commentators on both TikTok and Instagram see both sides of the conflict.

Many feel deeply heard through Ngo’s openness of her struggles with finding a healthy boundary with her parents that allows her to honor them while not feeling overly relied upon. Some of these supportive messages retell their own struggles with their parents’ hyper-dependence. In a follow-up TikTok, Ngo makes it clear that she is using her platform to voice these struggles that she has had with her own parents for others to recognize themselves in a position similar to hers (Ngo, 2023). Due to the cultural and generational gap, children of immigrant parents are the first generation in various environments—whether that be in education, immigration, nationality, and profession—and often have grown adept at adapting to new surroundings. This imposes the responsibility on the descendant to provide a smooth transition into inhabiting this foreign land for their family. But, being born into these circumstances should not dictate a life of continuous submission to the will of parents.

However, many do not agree with Ngo’s sentiment and that of affirming commenters. They argue that immigrant parents have had their own share of struggles that are immeasurable and deserve to be honored by simply doing what is being asked of them. Simple tasks such as turning on the TV or booking appointments should not infuriate first-generation children because they are indebted to their parents. After all, everything they have done, all the sacrifices they have made, has been for their children to have a better life than the ones they had. From their perspective, immigrant parents may feel ashamed that they need to ask for help, so using their “incompetence” may be their way of reshaping their lack of knowledge or request for help. Parents are figures of authority who were raised in a different time with disparate cultural values that may not coincide with the perspectives of now. Perhaps, the consensual initiative is to treat parents with more patience, knowing that they could be having difficulties with voicing their needs, and guiding them with instructions on how to accomplish the tasks that are within their capabilities. To illustrate, it is also our parent’s first life; it is also their first time navigating parenthood. Although there is always more work to be done, children of any generation of immigrant parents do not see the generational traumas our parents have broken from their parents, our grandparents.

I want to reemphasize that Ngo’s experience is not exclusive to the Vietnamese community, nor that of the Asian population at large. Weaponizing incompetence in whatever form it may exhibit is cut from the same fabric that causes first generation guilt from generational traumas. As a first generation Mexican-American, I find that this should be a conversation that all descendants of immigrants should have in reflection of the relationships we have with our parents. No matter the position people take on the topic of potential weaponized incompetence, it is important to approach this topic with sensitivity, because the relationship between parent and child is not one to generalize nor make assumptions about.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!