UFW’s Presence at UCLA Reveals the Struggle of Student Organizing

Photo by Evelyn Castillo

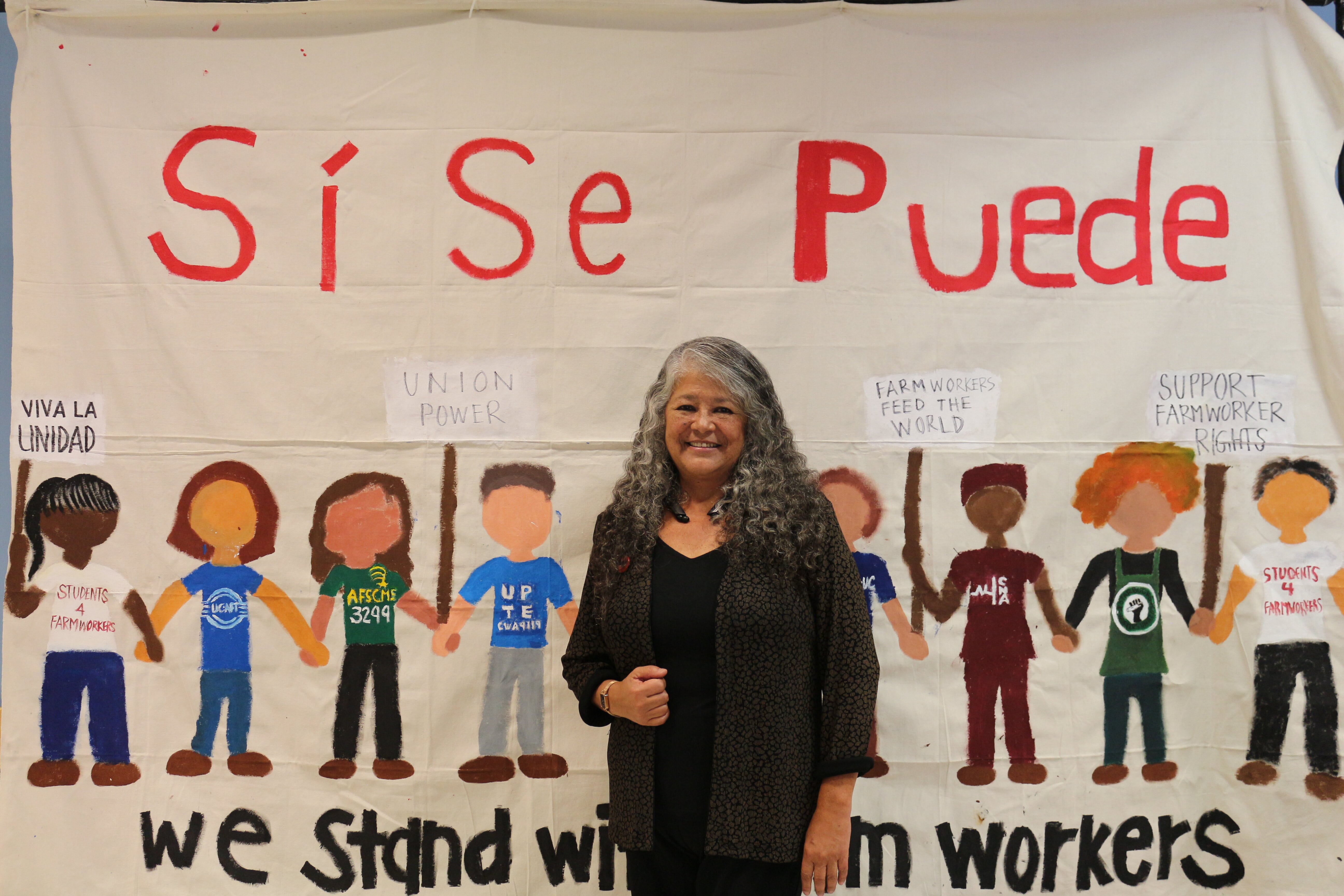

“Si se puede!” vibrates the walls of UCLA’s Bruin Viewpoint Room on April 24th, 2024, where hundreds have gathered in support of a student-organized labor rally. The chants, repeating in both Spanish and English, creates a nostalgic feeling, drawing back to the height of the Chicano movement of the 1970s and ‘80s. These feelings are intensified by the presence of Theresa Romero, the United Farm Workers (UFW) current president.

The UFW was founded by Cesar E. Chavez, Dolores Huerta, and Philip Vera Cruz in 1962 due to the decades-long exploitation of farmworkers in the United States, the majority being Latino and Filipino immigrants. The Bracero program, founded in 1942 during WWII, welcomed Mexican migrant workers with the expectation that they would leave the U.S. once their work was completed, while simultaneously holding them hostage to abusive working conditions during their duration in the States. Braceros were recruited with the guarantee that they would be provided with “transportation, living expenses, lodging, medical care and repatriation as well as wages the same as those paid for similar work to other agricultural laborers under the same condition within the same area.” Of course, American corporations did not uphold these standards, forcing Braceros to live in crowded, inhumane, and unsanitary housing conditions, with hidden fees for housing, food, and transportation not detailed in their contracts. Additionally, contractors heavily abused Braceros given their vulnerability for deportation, forcing them to work for up to 14 hours a day in grueling hot conditions, increasing their exposure to heat related illnesses and deaths. Farmworkers were “valued as nothing more than a cheap business expenditure, as opposed to human beings.” As a result, the UFW organized successful strikes and boycotts, including the five-year-long grape boycott and fighting for farm worker rights. Its influence extended beyond the fields into Chicano youth, fueling the Chicano Youth Movement. A noticeable result was the establishment of the Cesar E. Chavez Department of Chicana/o and Central American Studies here at UCLA, which was named in Chavez’s honor for his “use of hunger strikes as a method of resistance.” However, its reign of success eventually descended as Chavez’s controversial actions began to rock the UFW. Including: Philip Vera Cruz’s exit from the UFW due to Chavez’s disregard for Filipino workers and rights, and the establishment of Chavez’s “Illegals Campaign” where he firmly opposed the presence of “wetbacks” going to the extend of supporting the creation of a private Border Patrol within the UFW. With the UFW’s presence fading from mainstream politics, companies quickly moved to revoke all the policies the UFW had helped pass.

Conditions have therefore worsened since then, and presently, farmworkers across the nation have been deemed the exploitable labor force of this century. Their presence is often overlooked despite their large number, particularly in California, where the estimated number of farm workers ranges between 500,000-800,000 workers. The majority of these workers live in poverty (73%), are undocumented (75%), with their primary language being Spanish (89%). Despite having some workers’ rights in place granted by the National Labor Relation Board, the Department of Labor, the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, they are either a.) not federally strong enough to actually protect workers, or b.) not enforced by corporations. Because the majority of farm workers are undocumented migrants, the looming fear of deportation and imprisonment prevents farm workers from reporting instances of abuse, which corporations take to their advantage.

Agricultural and capitalist powers want to keep farm workers silent because otherwise, it would mean billion-dollar entities would have to pay fair wages, enact safe working conditions, and ultimately disrupt a system that only benefits them. The lack of knowledge about farm worker and migrant worker struggle is evident in UCLA’s current student and faculty body and is one of the main reasons this labor rally was organized in the first place.

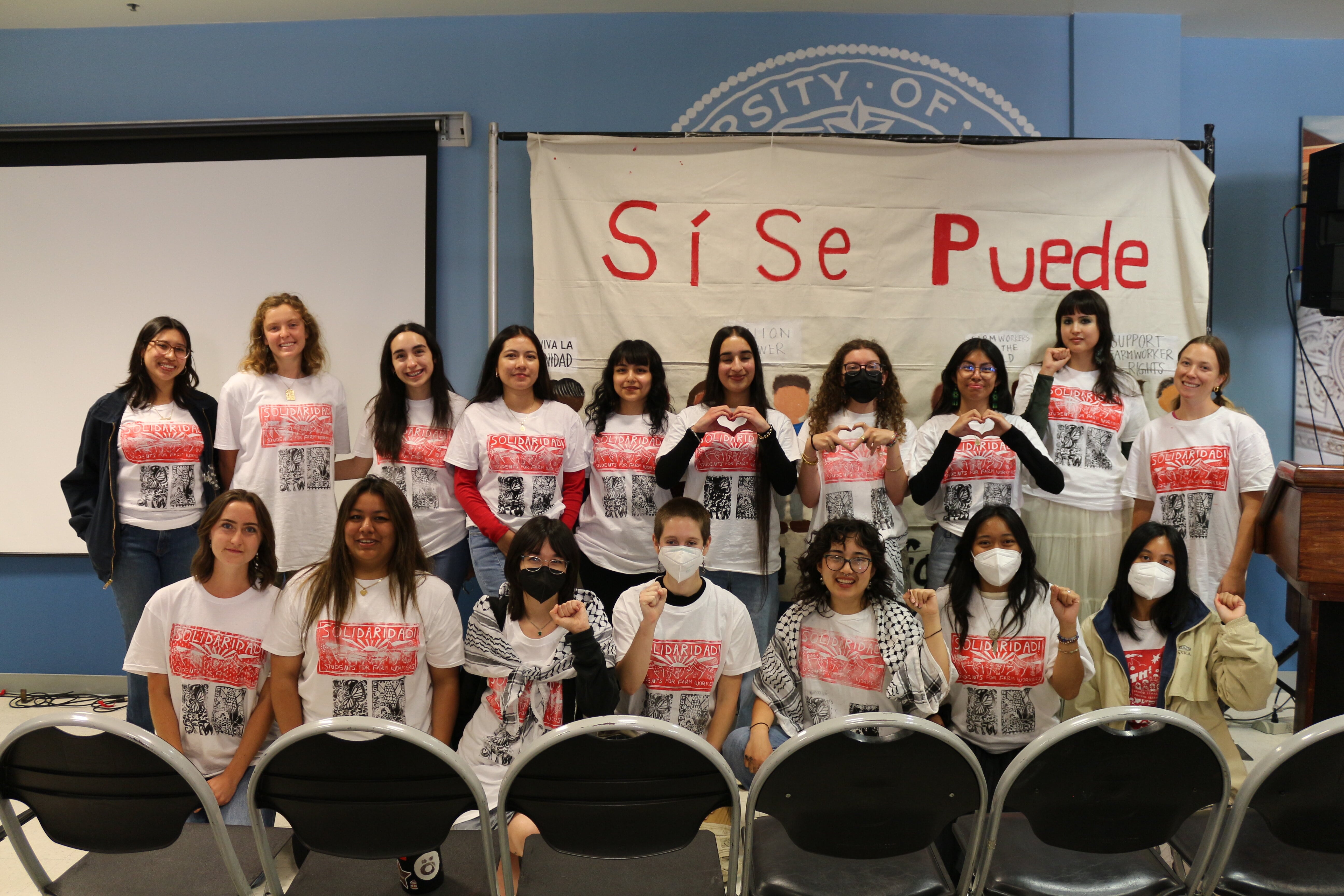

Six organizations–Students for Farm Workers (SFFW), COMPAS, Student Labor Advocacy Project (SLAP), Westwood Food Co-op, CA-League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC), and Anakbayan–in collaboration with Larry Frank, Special Project Manager at UCLA Labor Studies Center, spent two quarters planning the event. I had the pleasure of interviewing four representatives: Jocelyn Perez (she/her), Core Organizer of SFFW, Elizabeth Petrick (she/her), Co-Director of the Advocacy Committee at COMPAS, Hanna Reyes (they/them), Labor Solidarity Secretary of SLAP, and Diana Perez (she/her), Co-President of LULAC.

The interviews revealed the long and tedious process that went into planning such a large-scale event. I asked Jocelyn Perez, the main organizer, how it first began. She stated, “[Student for Farm Workers] met Larry Frank, who works at the UCLA Labor Center, [and] we got to learn that he organized back in the eighties with the UFW, especially during the boycotts…We started brainstorming ideas. So the first idea was to have a fundraiser for the UFW, led by a coalition of student organizations, and then secondly, to have a rally following that fundraiser where we actually bring Theresa [Romero] to campus. And, have a community space where we really bring in awareness and having call to actions for people to really get involved.”

Despite Jocelyn originally working with Larry, a faculty member, both recognized the importance of these events being student led. As a result, the six organizations (listed above) began to meet every other Friday for two quarters, with Larry Frank in attendance, distributing assignments to representatives, contacting unions, creating artwork, and advertising the event. Their motivation for the never-ending work among the representatives I interviewed is fueled by this similar sentiment: they came from migrant worker families.

Diana states, “I’m from the Central Valley. So I grew up around a lot of farm workers. My family worked in the fields, everybody in the Central Valley works in the fields…That’s our culture. So, coming to UCLA, it was really important for me to just learn more about like the social aspects that led us to be in that economic situation.” Elizabeth shared a similar experience, explaining that her grandmother was a farm worker, organizing alongside the UFW during the ‘80s. Hanna and Jocelyn, although not from farmworker families, have immigrant parents and families, and therefore understood and related to the labor struggle.

With a focus on the farm worker struggle, it begs the question: “Why do we need a labor rally like this at UCLA, considering we aren’t in the Central Valley?” In response to this, Elizabeth pointed out the obvious, stating, “The majority of students at UCLA live in a bubble. They don’t really understand where their food comes from or what goes into getting it on their table.” Jocelyn followed up by explaining that COMPAS conducted a study for Undergraduate Research Week where they found that the majority of UCLA students believed that the farm worker salary ranged from $60,000 to $150,000. The stark reality is that “21% of farmworkers live in poverty and the median income for farm workers is between $20,000 and $24,999.” As unfortunate as it may seem, the ignorance from UCLA’s general student body seems to be the overall drive for the labor rally.

Building from a place of ignorance, I knew that these student organizers faced numerous setbacks, both from students and UCLA Administration. I asked, “What barriers have you faced as a student organizer?” Answers varied, ranging from Jocelyn’s experience where an ASUCLA Catering representative repeatedly dismissed her attempts at accessing a required form to waive ASUCLA Catering’s outrageous fees, forcing her to cancel all food at the event altogether, to Hanna’s discussion on the treatment of UC Divest and Students for Justice in Palestine organizers. Diana’s criticisms perfectly summarize my thoughts when I asked this question. She states, “I think UCLA is definitely built and catered to whiteness and wealth. It listens to money. Not even in just activism, but in classrooms too. The way teachers teach, the way we communicate, all of that just adds up and it gives you the sense that you are being pushed aside…[UCLA] just proves over and over again that POC clubs are being pushed aside, not given the finances we need, the support we need.”

(Our conversation on the topic, unknowingly to us, was foreshadowing the disgusting attacks on the Palestine Solidarity Encampment that occurred on Tuesday, April 30th, and the late evenings and early mornings of Wednesday, May 1st, 2024, and Thursday, May 2nd, 2024. In addition, unlawful arrests were carried out on Monday morning, May 6th, 2024. Despite this piece originally focusing on the April 24th Labor Rally, it would be hypocritical of me not to include a student perspective on the attacks, given that I am writing on student organizing. UCLA, Chancellor Gene Block, UC President Michael Drake, and the administration solidified its stance on preserving “whiteness and wealth”–as Diana put it– over human life. On April 30th, UCLA allowed Zionists to attack the encampment by throwing fireworks, spraying pepper spray, bear mace, and tear gas at students, and physically attacking students with wooden bats and planks, leaving hundreds of students mentally and physically traumatized. On May 2nd, law enforcement ordered by UCLA raided the encampment, brutalizing students with rubber bullets, flash bangs, and smoke bombs. Over 200 Pro-Palestinian protestors were arrested, including students, staff, faculty, and community supporters. On May 6th, 44 students and spectators were arrested, initially charged for breaking a curfew, then later for conspiracy to commit burglary. Meanwhile, only one Zionistattacker has been arrested as of the writing of this article.)*

Diana’s comment reminded me of the position in which low-income students, queer students, and students of color are consistently put in. We are meant to be students. We came to this institution to learn, gain experience, and embrace our new-found identities as young adults. However, we are forced into positions of organizing. We shouldn’t be “fixing” problems that should not exist in the first place; we are meant to focus on our education. The U.S. is founded on a structure of dispossession, white supremacy, wealth and property accumulation, and gendered violence. Those same structures are deeply rooted in our society; they become our “common sense,” resulting in new systems reflecting those same structures. The military industrial complex, urban planning, the agricultural system, the immigrant system, the education system, etc. reflect the previously mentioned structures of oppression.

UCLA markets itself as “committed to discovery and innovation, creative and collaborative achievements, debate and critical inquiry, in an open and inclusive environment that nurtures the growth and development of all faculty, students, administration and staff.” Instead, students are put in positions where we constantly combat entities meant to suppress us, with little to no support. (Or we get arrested for doing so!)*

Hanna elaborated on how hard it can be to juggle such a daunting task. They stated, “A lot of [us] are battling through personal issues, financial issues, and then having to work like two jobs while also balancing classes. And it’s like, how do you even have the time to go to office hours and ask for help? You don’t even have the time. You’re tired.”

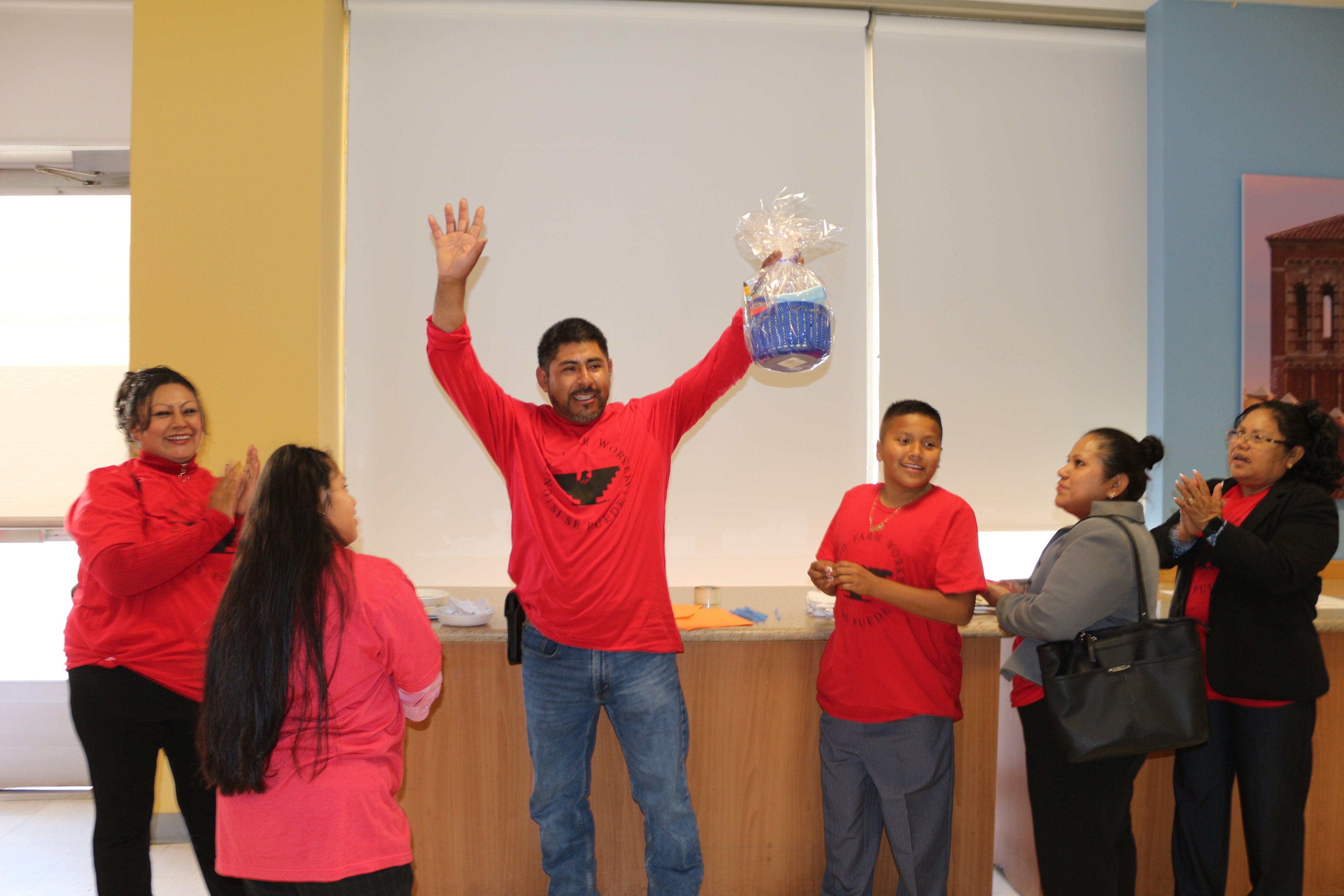

Simply put, it does get tiring. But we cannot allow an institution, nor the exasperating helplessness we may feel, bar us from progressing forward. Accomplishments, no matter how big or small, are constant reminders that student organizing cultivates beautiful results. The labor rally and the encampment* are examples of them. Thanks to student organizers, the UFW raised the minimum fundraising goal of $10,000, dozens of students signed up for UFW legal training, and farm worker testimony was brought to a non-farm worker city. (Regarding the encampment, there was a noticeable increase in Pro-Palestinian unity, students became more aware of UCLA’s violent past and present, and the United Auto Workers have voted for a strike.)* Despite the difficult situations student organizers and students are placed in, there is no change without action. We live with the constant reminder that we shouldn’t be doing this in the first place. We should not be fighting for recognition, resources, and help at our own “#1 public university.” However, as tragic and dystopian as this reality may be, it must be us who fix it, as so many like us, whether that be UFW or other, have tried to do before.

*Added in after the events of April 30th, May 1st, and May 6th, 2024.

Photo by Evelyn Castillo

Photo by Evelyn Castillo

Photo by Evelyn Castillo

Photo by Evelyn Castillo

Photo by Evelyn Castillo

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!