The Power of Counter-Storytelling: Honoring the History of Marginalized Communities

Visual by: Melissa Morales

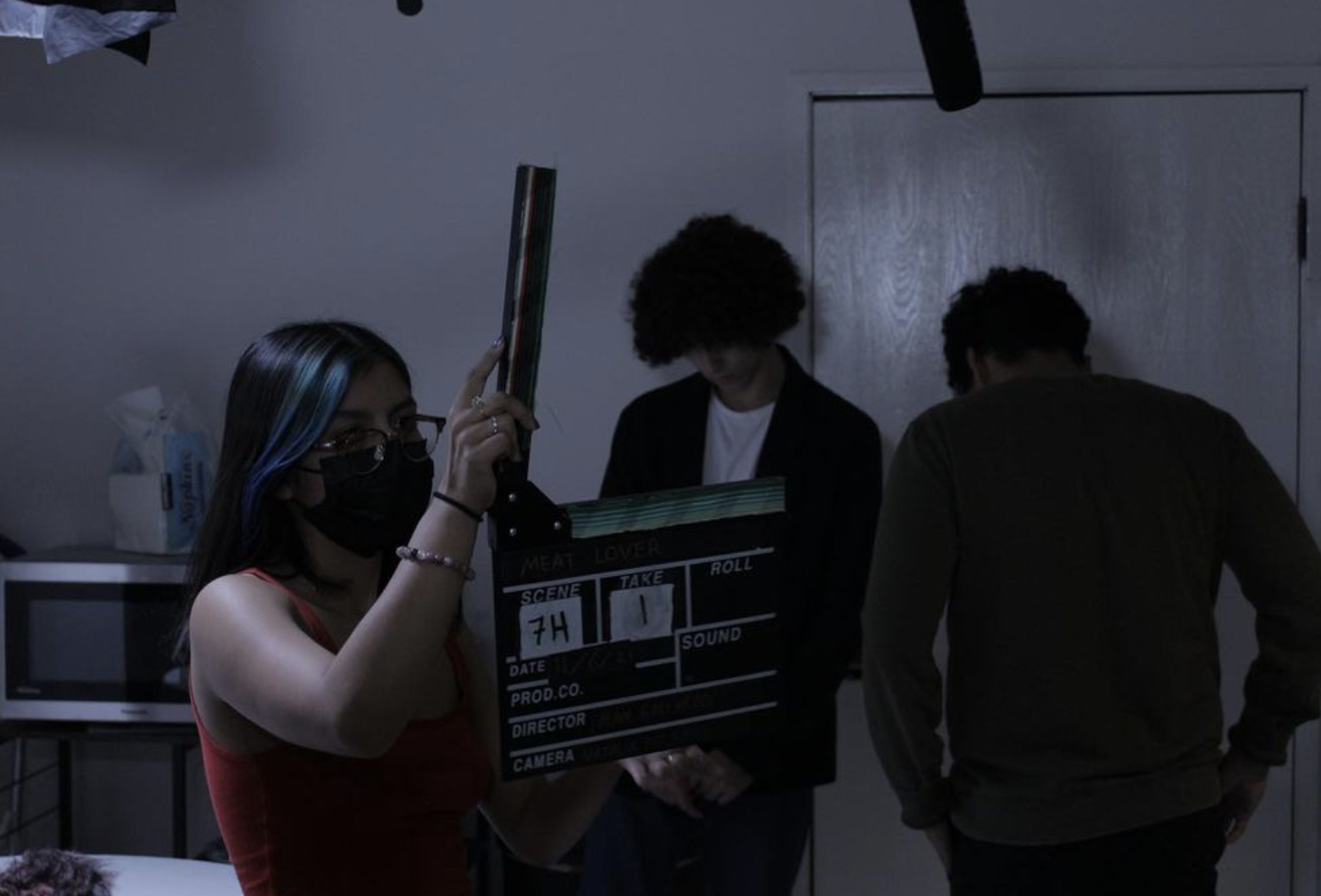

Counter-storytelling is a method of communicating the experiences of racially and socially marginalized people—a direct contrast to the dominant narratives promulgated by those in a place of social and racial privilege. Effectively, counterstories unveil the realities of oppressed communities which have often been distorted or omitted altogether.

Traditionally, mainstream storytelling through mass media and academia has led people to internalize incomplete truths about American history. I, for one, failed to recognize that the history I was taught was revisionist in nature. For the longest time, I blindly believed narratives such as Manifest Destiny or the idea that the Civil War was fought solely over the immorality of slavery. It was not until I came in contact with their counterstories that I realized how deficient these accounts were. Conversely, counter-storytelling reexamines America’s history in a manner that acknowledges and validates the current experiences of marginalized communities.

Counter-narratives can be found in historical texts such as An Indigenous Peoples’ History of the United States, wherein author Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz provides an alternate view of Manifest Destiny. She evaluates how the dominant narrative surrounding settler colonialism and the aforementioned doctrine omitted the gruesome violence and slaughter inflicted onto the Indigenous populations. of the U.S. The exclusion of such details pushes people to look past the dispossession of Native Americans so that we can revel in America’s accomplishments. Rather than giving in to the belief that Manifest Destiny was inevitable and justifiable, Dunbar-Ortiz sees it as an excuse for genocide. Consequently, her writing opens a space for reflection on the subjugation of Indigenous peoples, one that renders a more holistic understanding of the atrocities their communities have been subject to.

Moreover, counterstories can also take shape in autobiographies. For instance, in Assata (Shakur): An Autobiography, Shakur revisits the glorified dominant narrative surrounding Abraham Lincoln’s dedication to abolishing slavery. She clarifies that at their core, the problems between the North and South were economic, not moral in nature. Correspondingly, she finds that Abraham Lincoln’s concern did not stem from humanitarian regard for those enslaved as most might be inclined to believe. In line with this realization, Shakur notes how such misconceptions about the history of marginalized people in the United States have led many to believe that this country is evolving in a slow, but steady linear progression towards equality. The belief in this dominant narrative causes us to make critical mistakes in assessing our current situation, oftentimes resulting in an inaccurate and rose-tinted perception of the world.

Consequently, works such as those of Dunbar-Ortiz and Shakur help expose the harmful dominant narratives which conceal and undermine Indigenous and Black history respectively. These counterstories provide readers with a more complete understanding of America’s history, and they factor in the very groups that are often absent from the accounts of events that directly impacted them.

Perhaps even more alarming though, is the power of dominant narratives to perpetuate false stereotypes about minority groups. For instance, there is this common misconception that the Latinx community does not value education—one that I, unfortunately, fell prey to when I was younger. While the belief was born from the prejudice of others, it did fundamentally shape my view of my own people and fractured my Mexican-American identity.

However, counter-storytelling proved to be my personal remedy. Case in point, the East LA Blowouts of 1968 demonstrated that the Chicanx community valued education more than anything, and it was racism and institutional barriers that hindered their academic progress. This event has been continuously referenced to challenge the aforementioned dominant narrative.

At the time, Mexican-American students throughout the Southwest had a 60% high school dropout rate. Students were subjected to prejudice from teachers and administrators who stereotyped Chicanx students and discouraged them from pursuing higher education. In order to combat these injustices, young Mexican-American activists led school walkouts to demand equal and qualitative education.

The Blowouts were the largest mobilization of Chicanx youth leaders in Los Angeles history, many of whom have shared their counterstories. In the article, “Grassroots Leadership Reconceptualized: Chicana Oral Histories and the 1968 East Los Angeles School Blowouts,” author Dolores Delgado Bernal documents the experiences of those involved in the walkouts. For example, Rosalinda Méndez González, a former student, recounts the oppressive racial climate within her former school. She notes that teachers would call them “dirty Mexicans” and urge them to return to their country while the classrooms were noticeably underfunded. Her oral history is just one of many accounts that demonstrate that the Chicanx community was not apathetic about education. Instead, they suffered as a consequence of the indifference and inefficacy of those responsible for their learning.

Ultimately, it was through counter-storytelling that I learned about my history, that I abandoned the false and negative images associated with being Mexican-American in this country. Counterstories are very much the foil to harmful dominant narratives insofar as they allow us to reexamine and challenge incomplete and sometimes, altogether baseless views. Moreover, counterstories raise our critical consciousness about injustice and inspire an exploratory attitude of the world wherein we consistently analyze history in a more holistic and truthful manner.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!