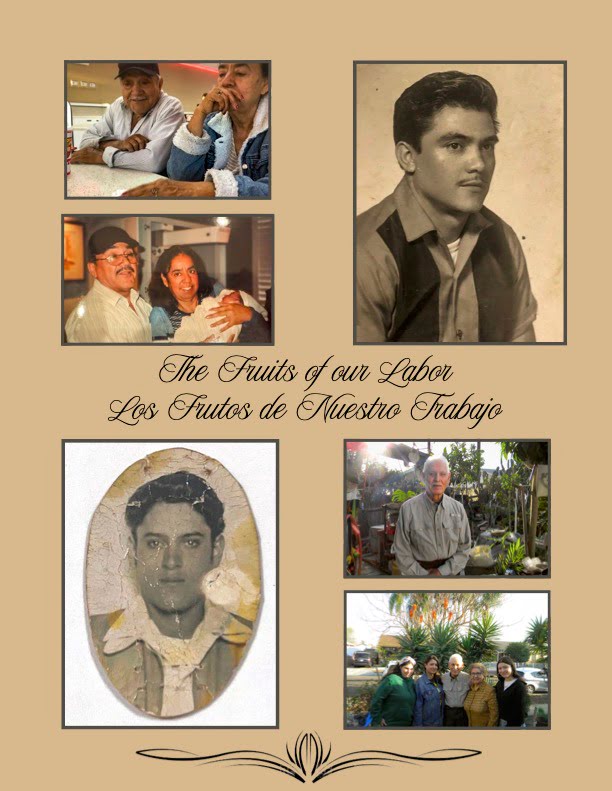

The Fruits of Our Labor

Photos provided by Marissa Bermudez and Olivia Zepeda. Designed by Marissa Bermudez

Between 1942 and 1964, more than 4 million braceros—“temporary” workers from rural areas of México— entered the United States with legal contracts. They were hired to work in the agriculture and railroad industries across the country. These were physical laborers, who picked the strawberries, lettuce, cotton, chiles and peaches that supplied all grocery stores across the country and built the railroads that transported these goods.

Salvador Casas Varela, my grandfather, was 19 years old when he became a bracero, and 68 years later he can still recount the back-breaking work of picking the crops I just mentioned. He was born in December 1938 in Rojas, Nombre de Dios, Durango, México. As one of the eldest of six siblings, he was expected to provide for the family. Señor Varela first immigrated to the United States with his father, who showed him how to cross the Southwest border illegally. Rosendo Cabral—born in June 1936 in Cueva Grande, Valparaíso, Zacatecas—became a bracero at the age of 20. Similarly, Señor Cabral followed the example of his father and immigrated to the U.S. in order to work in agriculture to support his family back home. The oral history of Señor Cabral was so graciously provided by Marissa Bermudez, one of La Gente’s visual staff.

The oral histories of our grandfathers are a testimony to how the demand for exploitable labor categorized an entire group of people, shaping their political identity long after the conclusion of the Bracero Program. I use moments from their stories and the written history of experts to reveal how labor is central to our identity and expose how the U.S. has used that to further exploit undocumented migrants.

Señor Varela first immigrated to the U.S. from his pueblo on Mexican Independence Day in 1957 when he was 19 years old. At 5 in the afternoon, he snuck onto the back of a train, sitting on the steps just inches above the ground as it rushed underneath the train car. According to Señor Varela, he spent “the whole day enclosed, and it was at least 100 degrees” in the train. He wasn’t alone. Señor Varela was part of a large group of poor, unmarried men immigrating to the U.S. to look for work promised by the Bracero Program, which was implemented to remedy the lack of workers following World War II. The train would take all its unticketed passengers to Mexicali, donde lo contrataban in Calexico before they were taken to Santa Ana, California. As he sat in the train, Señor Varela recalled, que se sintió triste. He remembered thinking, look at where I’m at, while my whole neighborhood is over there, everyone dancing and dancing for the country’s national festivities.

In Santa Ana, he picked chiles within a 20-meter-long field. His job was to throw the chiles into a truck that rolled alongside them while quickly walking in front of a machine. He was unable to pause for breaks because “the band [on the machine] would take you” if you stopped long enough. Señor Varela recalls his back hurting since childhood; his work had always required him to be bent over. Still, he knew he had to fight the pain to get the work done.

Señor Cabral first traveled to a hiring center in Palma, Sonora, via truck from Fresnillo, Zacatecas, before the group boarded a train to Mexicali. Once contracted, he entered the U.S. legally to work mostly vegetable fields, picking celery, carrots, lettuce, tomatoes and strawberries in Salinas, California, for 6 months at a time. When there was no work available, Señor Cabral was allowed to return to México for months at a time. In 1961, he returned as a bracero once more, this time picking oranges, lemons and grapefruit in Santa Paula, California.

Señor Varela remembers being around what felt like 2 million people, waiting days to pass into the U.S. At a center located near El Paso del Águila—a place for frequent crossing along the border between México and Texas—Señor Varela was told to line up along a rack, where he was “fumigated” as part of a long process to determine his eligibility to be contracted for work. Throughout the duration of the Bracero Program (1942-1964), 4.7 million braceros would have gone through something similar, trekking to the U.S.-Mexico border by any means necessary in hopes of getting temporarily contracted to work in the agricultural industry and then undergoing the invasive examination required to proceed.

National sentiment racialized Mexican migrants as dirty and diseased, yet the greed for max profits kept the demand for Mexican bodies high. Señor Cabral recalls the need for thousands of people to pick lettuce. Though he was initially not chosen to work because his “hands didn’t have calluses,” eventually the demand outweighed employers’ specific interest in certain individuals. This requirement further illustrates that the U.S. government and its industries were looking for individuals who “proved” they were hard-working over the wellness and overall conditions of farmworkers.

In multiple conversations with Señor Varela, including his oral history interview, I’ve asked him how he felt about this maltreatment of Mexican immigrants. He reflects on this experience as a “tremendous history,” saying God has helped keep him alive, when he really considered what he had been through. His hesitation before answering this question makes me wonder whether he chooses to censor himself for my sake or his own. While he can state matter-of-factly the inhumane treatment he was put through, including the fumigation meant to cleanse him of any contamination, it is apparent that it’s a lot harder for him to understand why he was treated this way.

A prominent norm in Mexican culture is to be grateful for, content with what you have, and never ask for more. Indeed, I acknowledge its influence on the way my grandfather feels indebted to the great power that granted his family this opportunity at a better life—so much so that he is unable to criticize the government that mistreated him for years, incarcerated and then deported him, and racialized him with negative stereotypes. Still, he attributes his survival to God’s graces.

As a seasonal worker in the fields of California and Texas, Señor Varela would go back to México after his contract had ended and return to the United States when a new season began. However, he faced a big problem: no matter how long he had worked in the U.S., his “mica had not arrived.” Señor Varela understood that without a mica, referring to a green card, he would have to face the difficulty of returning to the U.S. without proper documentation.

The problem was larger than him. While the Bracero Program aimed to control the constant stream of undocumented Mexican workers, providing over 4.5 million work permits, it was clear that the number of undocumented immigrants surpassed the number provided for the Bracero Program; only 4-7% of braceros entered legally. This was possible due to the loose sanctions of the open border that allowed employers to hire many undocumented Mexicans. That’s when Señor Varela decided it would be better to live in the U.S., so he wouldn’t have to continue to cross between countries with everyone else. Now, he needed a reason to stay.

When the Bracero Program ended in the 1960s, my grandfather finally found himself in Los Angeles, where he tried to find work with no success. One day, he met a man at a Dodgers game who offered to recommend him for a job working in an upholstery factory. Soon after, Señor Varela began work screwing legs onto chairs in an assembly line. Although the job was difficult, it was bearable because, for the first time, he had found steady work and pay. He remembers this moment of his life fondly: “One day I made it, and I lasted eight years making furniture. And that day changed everything for me and my wife and kids.”

As a farmworker, my grandfather was subjected to inhumane living and working conditions; braceros’ work was often unpaid and they lacked the ability to challenge their abuse. Without a union— given if he refused to work—he could be reported to immigration officers and deported. Unlike farm work in which his housing, meals and pay depended on the season’s harvest, working in a factory provided more stability. He had the security of work and pay every day. Finally, Señor Varela was able to stay in the United States.

This did not come without sacrifice, either. He reflects on his journey up to this point, remembering that “it was very difficult—[He] never got to visit [his] children… [he] didn’t even witness their births.” The United States government’s classification of Mexican laborers as expendable labor prevented many from seeing bracero workers as equal humans deserving of fair treatment. Braceros were exploited for their work and separated from their families, yet my grandfather still remembers the opportunity to work fondly. After all he endured up to this point, it was starting to look up for him. He finally had a steady job after years of the gamble of finding work.

In 1983, Señor Varela was finally able to get his citizenship. He was now 45 years old. According to him, citizenship cost him hours of studying American history, “more than $50, at least 1,000 pesos,” and he was required to bring “two American character witnesses”. He brought a Mexican friend, who had become a citizen recently. The other he had known for only three years, and he can’t remember where they met. Señor Varela attributes much of his success to the kindness of others, claiming, “for everything I have done, people have always helped me to do it”. Although his “English was very chopped,” he was grateful for the kindness of the lady who interviewed him and her effort to understand him.

Señor Varela wasted no time in finding a lawyer to help him move his brothers into the United States from México. Once again, he attributes his success to the good graces of individuals who were willing to help: “[The attorney] said ‘bring them.’ And every three months I had another brother in the United States.” Citizenship was not an easy thing to gain. Although being a bracero helped Señor Varela and Señor Cabral earn enough money to start the process, both men were unable to receive citizenship for years due to troubles with lawyers and citizenship tests. Regardless, they both had to persevere, since they were expected to also arrange papers for their siblings and family members.

Having citizenship didn’t fix everything for Señor Varela. His family, which he succeeded in bringing to the U.S. in the late 1970s, lived in poverty. Señor Varela was only able to rent the garage of a kind woman in Hawthorne for him and his family. Many of their neighbors dealt drugs to gangs in the area and they were often harassed by local gang members. When he reminisces about LA in the ‘80s, though, he can’t help but think “¡ay, que bonito!” LA was still beautiful. Despite the difficulties, Señor Varela found the trouble worth it because “this country is rich,” and he was “able to find work that paid” him. These social issues of Los Angeles seemed trivial to what he had experienced in his lifetime. The only thing that mattered most was having enough work to make money for his family.

Almost 5 million Mexicans of mixed documentation status were brought into the United States throughout the years the program operated, changing the attitudes about immigration in Los Angeles. The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 allowed employers to hire undocumented workers. This caused an influx of undocumented Mexicans (called wetbacks), encouraged by growers who benefited from exploiting their labor, but was simultaneously criticized by Mexicans already living in the U.S., who blamed braceros and wetbacks for their poor economic conditions. When Señor Varela immigrated to the United States, it was “something special” because people were willing to help each other out. Likewise, Señor Cabral shared the same sentiment; “the people that God put on [his] path were good,” and they taught him how the system, laws and rules worked in the United States.

In comparison, the polarization that exists today, in Señor Varela’s opinion, is due to “the conflict between Republicans and Democrats [who] have not tried to unite,” and therefore, are always fighting. As a result, politics became very individualistic; everyone is in it for themselves, and that, to my grandfather, is why this “problem has led to all our other problems.” Even though the Bracero Program provided many Mexican immigrants with work and a pathway to citizenship, it also created tension between many political groups in the United States.

The immigration policies have evolved since the executive order birthing the Bracero Program in 1942, making it harder for immigrants to receive the same opportunities that were available to Señor Varela and Señor Cabral 70 years ago. Even so, many continue to sacrifice, enduring persisting racial discrimination, hoping for a chance at achieving the same economic success that was available to braceros decades ago. Señor Varela remembers his immigration story as a beautiful thing, despite all the difficulties he faced, as he is able to live happily with his family united because of it. He only hopes that those debating its legalization see it for its potential to change people’s lives for the better.