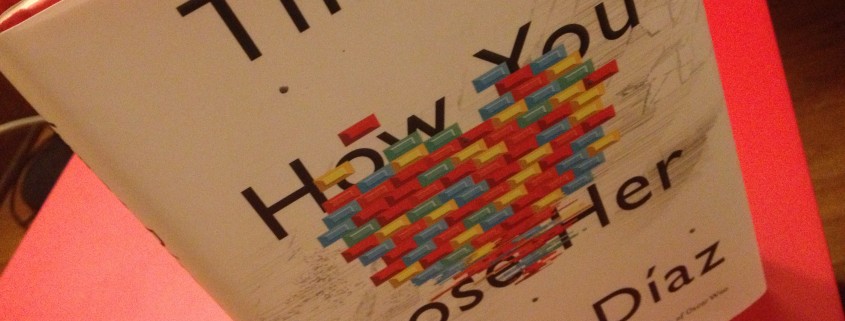

Para Los Enamorados, Solitarios, y Mujeriegos

On Junot Díaz’s This Is How You Lose Her

“Instead of lowering your head and coping it like a man, you pick up the journal as one might hold a baby’s beshatted diaper, as one might pinch a recently benutted condom. . . . Baby, you say, baby, this is part of my novel. This is how you lose her.”

In Junot Díaz’s book, This Is How You Lose Her, he presents us with raw, enthralling short stories of inconsistent, incomprehensible, and disloyal relationships. He shows the evocative power of love in various forms: maternal, brotherly, the immigrant and the homeland, and the irrepressible cheater. The dominant narrative, however, is that of “sucio,” “mujeriego,” Yunior—the protagonist dealing with life’s inevitable: love and loss.

I find that these stories of romantic failure are also unified through the difficulties we have in expressing, understanding, finding and letting go of love. How do people come to live a “half-life” of love—a life of longing, loving but not being loved? At what point do our lovers stop mattering to us? Do they really ever stop mattering? Cierto que cuando te enamoras, te enamoras para siempre?

This book analyzes the battle of our human desire, and looks at the heart’s weakness and the process of loving, losing, and repairing. Díaz conjures a realistic world of relatable, memorable characters and vicious, effectively lasting language. We see the psyche of a cheater, as this book really is the “cheaters guide to love,” and the instruction in how one manages to Lose Her.

A Sandra Cisneros love poem is the mini preface to Díaz’s book, setting the tone of temporary love and endless longing and ache that defines our relationships: “There should be stars for great wars like ours.”

In the first story we see Yunior’s inability to love his girlfriend Magda—who believes Dominicans are sucios—and where we realize not to anticipate much morality from him: “I’m not a bad guy. . . . I’m like everybody else: weak, full of mistakes, but basically good.” As he further recollects romantic experiences from childhood to adulthood, we see Yunior’s various women: “comic-book-reading” Alma, “white-trash” Flaca, high school teacher Miss Lora. In Yunior’s relationships we see condescending machismo, yet some nostalgic regret for what is done. Most importantly, many of Yunior’s relationships collapse when a lover finds strangely written documentation of his infidelity.

Díaz uses such aggressive, thrilling street language in his stories. He occasionally uses the commanding second person and the “I” voice. In combination, I think, both make this a psychologically interesting read, such that the narrative style is seemingly confessional, commanding, engaging to the reader as he or she follows the episodes of how hopeless Yunior loses in his dysfunctional relationships and becomes accountable for his emotional fallouts.

This book, to me, ultimately gives a poetic account of how some men manage their masculinity and of how real love, in all shapes, is not easily shed. This New York Times Bestseller is witty, haunting, and a must read for los enamorados, los solitarios, the mujeriegos, those that want love, and even those that hate love.

See what Junot is up to at www.junotdiaz.com.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!