Support for hunger strikers at Corcoran prison

Saturday July 13th I was at Corcoran State Prison, participating in a California statewide mobilization to support the ongoing prisoner hunger strike, which began July 8th with about 30,000 prisoners statewide refusing meals. This strike is to ultimately influence Governor Jerry Brown and the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) to improve California prison conditions. A petition has circulated and much action has been made to make this reform possible.

It was a 3-hour drive to the city of Corcoran from Chuco’s Justice Center in Inglewood, where I met up with a group of about 30 people made up of different races and ages and coming from organizations and cities all over Southern California. We took a bus to meet with what would turn out to be about 300 people rallying at the gates of Corcoran State Prison.

Speaking to people about the U.S. prison system, I find that many impose a stigma on prisoners. But this particular assemblage of demonstrators realize that the prison system is what’s incorrect, not the prisoners.

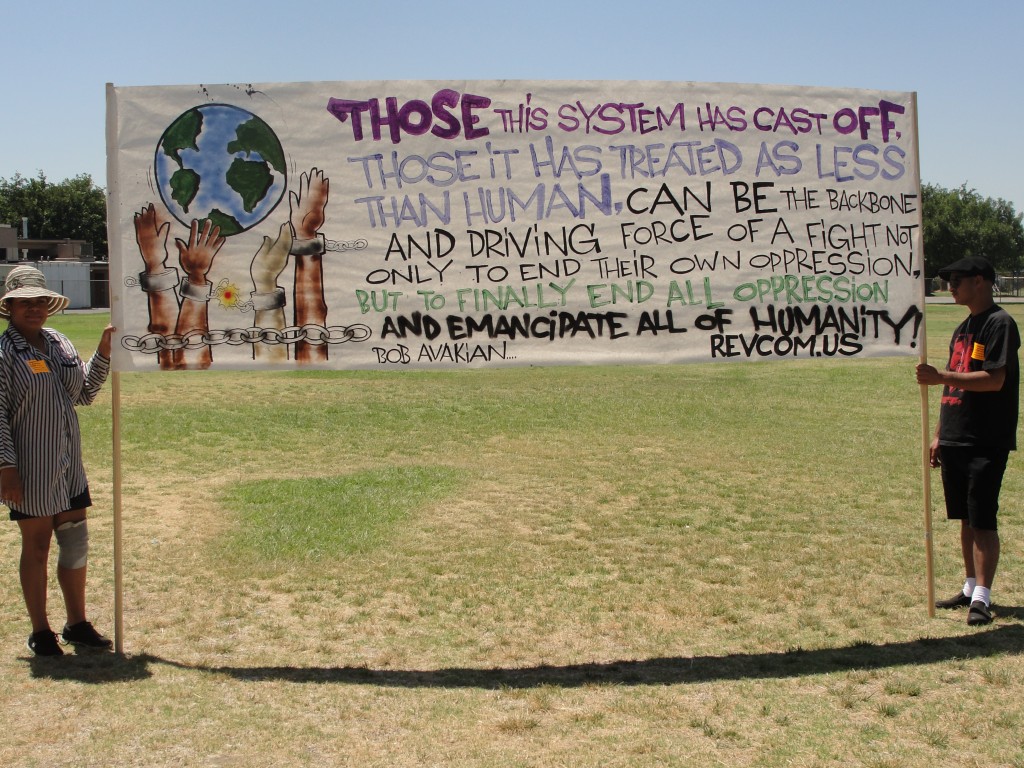

It was over 100 degrees when we arrived and gathered at a nearby park in the remote prison town of Corcoran. The park is a few miles away from the prison and from this park we would eventually march to the prison gates. Gente of all backgrounds met at the park to voice solidarity with the prisoners and their actions of resistance. People addressed not only the injustices and abuses in male incarceration, but also those in female, youth, immigrant, and refugee incarcerations. The demonstrators connected the prisoners’ hunger strike to larger issues. This strike addresses one aspect of an abusive system that needs change.

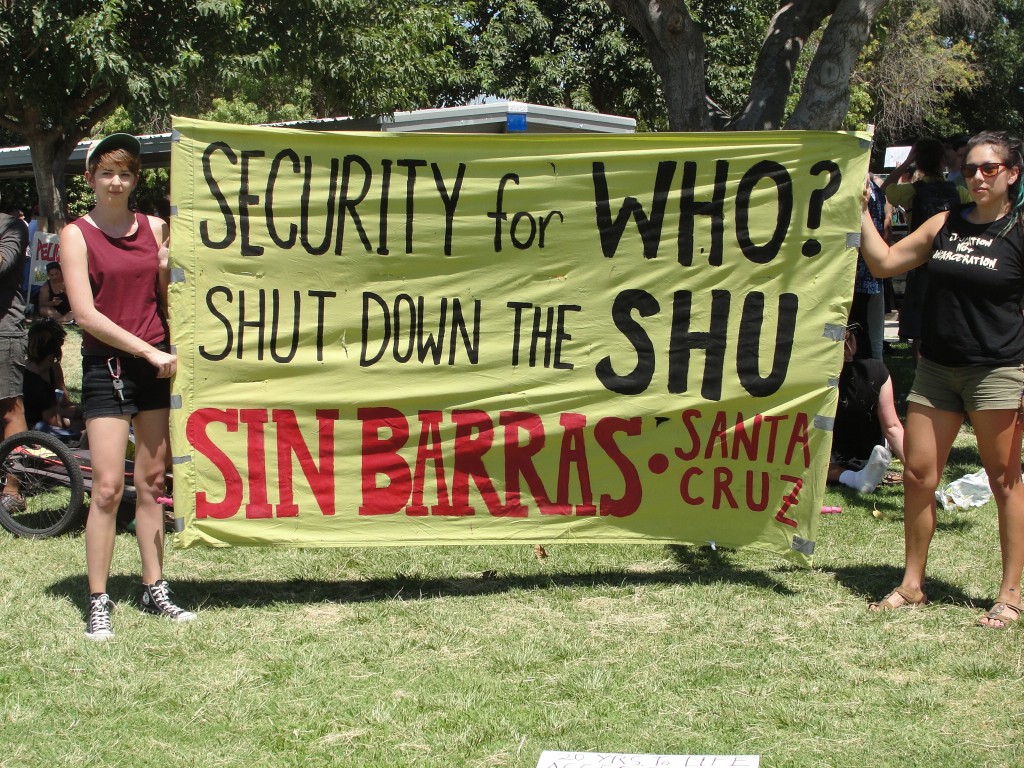

A danza indigena at the park kicked off the demonstration. Following it, we marched to the prison. Demonstration signs, flags, and chants brought a sense of liveliness to the prison town. Collectively, people demonstrated global resistance towards mass incarceration and torturous prison conditions. The most common demonstration sign had the prisoners’ 5 demands written on them: eliminating group punishment and administrative abuse, eliminating the debriefing policy and modifying gang status criteria, ending long-term solitary confinement, providing adequate and nutritious meals, and creating and expanding constructive programs for all prisoners.

A mother from San Diego marching with her children shared that her husband is in Pelican Bay State Prison’s Security Housing Unit (SHU). The time spent in a SHU cell (about 7 feet by 11 feet with no windows, sun, or fresh air) is typically long-term. It is segregated imprisonment for inmates usually considered high security risks, more specifically, for those suspected of being affiliated with a gang. However, what determines gang affiliation is quite arbitrary. The policy is very much flawed. The average time an inmate spends in the SHU is about 7 years.

According to prisoners’ case files the basis for SHU imprisonment includes reading revolutionary literature, speaking in particular language from one’s ethnic background, and briefly associating or interacting with gang members despite one’s non-affiliation. Such evidence was never reviewed by any external body. Following the 2011 prisoner hunger strike, the CDCR agreed to review the policy that forced many into the SHUs for such long-term isolation. Of about 400 reviewed, 200 were approved back into the general population. However, such attempt to improve policy has been ineffective. Population in the state’s SHUs has increased 15% in the recent year.

Her husband has spent more than 10 years in a SHU cell and has never done anything violent. She says that the hardest thing is not being able to touch him. In the Pelican Bay SHU, as in other SHUs, a prisoner is not allowed to make or receive phone calls and is not allowed to have contacted visits. Furthermore, they have no access to drug treatment programs and cannot attend religious services. Average time spent in the SHU is 22 hours a day. This isolation has impacts on prisoners’ mental and emotional health; some prisoners have been known to experience rage, depression, anxiety, hallucinations, and some have committed suicide. Moreover, some women in solitary confinement have been said to experience premature menopause and amenorrhea (an abnormal absence of menstruation).

At the demonstration, Margaret Prescod, host of Sojourner Truth on KPFK 90.7 FM, emphasized that women are victims of mass incarceration and torturous conditions as well. Single mothers are now one of the fastest growing populations entering prisons. Women had a big presence at this demonstration, too. Many brought to light the otherwise unrecognized forced sterilization (medical procedure that leaves a person unable to reproduce) of California female inmates. Prison medical staff pressured and targeted the women who they thought were likely to return to prison later on. Risk factors and reasoning for such procedures weren’t talked over with the female inmates. Arguably, this is a practice of genocide; it stunts future generations. Female inmates, like male inmates, are being denied their right to dignity and humanity.

Torturous conditions go unnoticed easily in the U.S. prison system, given that prisoners’ voices barely penetrate the walls that imprison them. A movement is slowly coming out of the prisons. However, much support and pressure is needed from those on the outside. One crucial element of this demonstration was to show that the prisoners have not been forgotten, that the outside, whether they have a loved one locked up or not, stands in solidarity with them. These conditions do not allow the opportunity for rehabilitation. Some will be released worst off than they were before entering.

Marching on the main road towards the prison, I soon began to think of my Tío and the time I visited him at prison in Victorville, CA. And I began to think of my Primo and our troubled childhoods, and how I managed to escape the youth of color school-to-prison system but he is still navigating and lingering in the system. Then, I hadn’t recognized the U.S. system that prevents my educational and economical growth. The U.S. has the highest youth incarceration rate in the world.

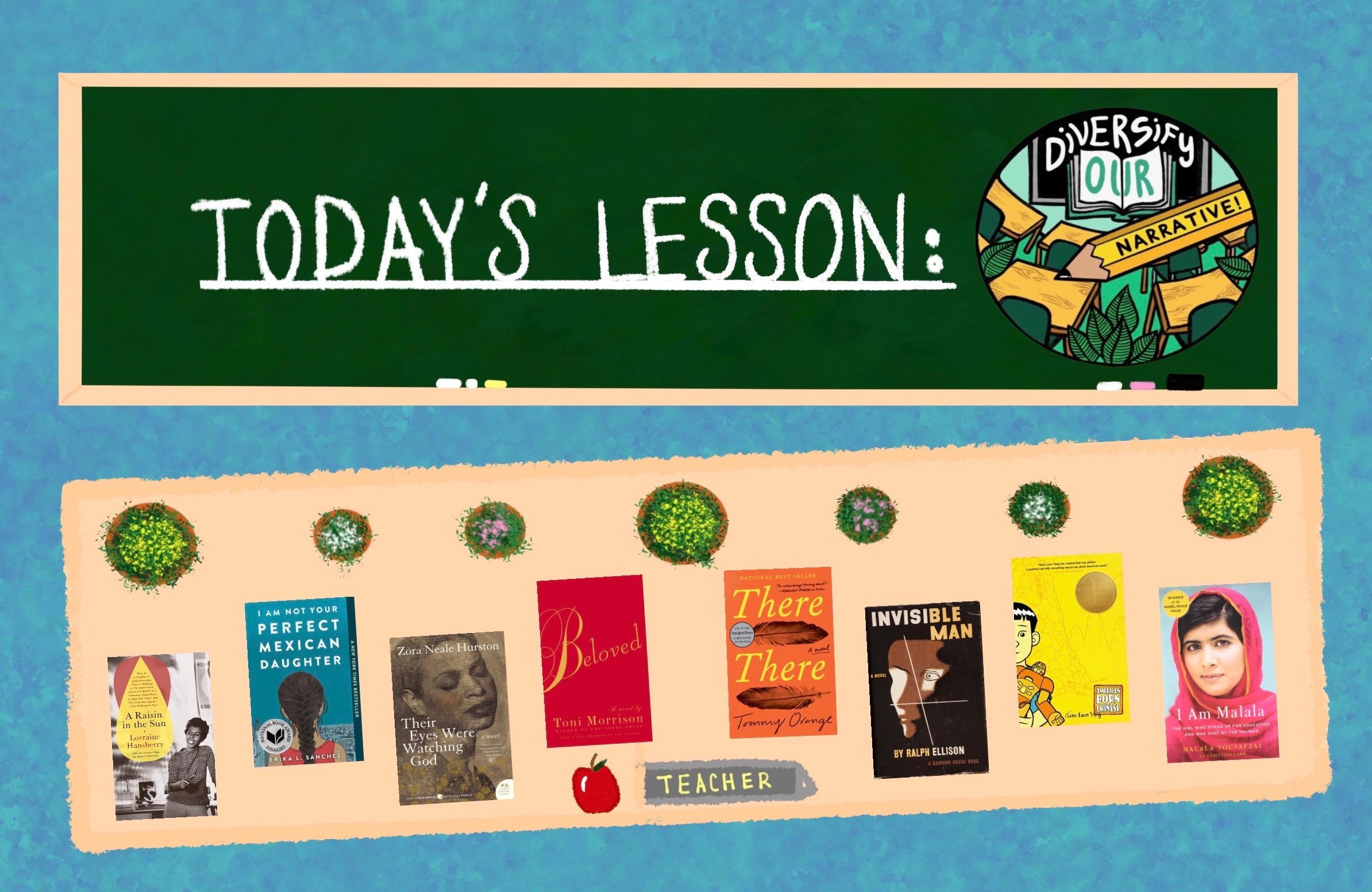

Research done by a collective of organizations concerning the crisis in juvenile justice, including the Youth Justice Coalition, shows that the U.S. spends more than $80,000 per year per youth on juvenile corrections facilities and no more than $11,000 per year per student in school. At schools with more students of color there is more likely to be zero-tolerance policies that ultimately result in expulsions and suspensions–the first encounter a youth of color has with corrections. The law enforcement in schools and the constant policing of youth of color has only grown. Society perpetuates injustice and criminal activity. Instead of investing in adequate and just reform, much investment is made in locking up people (for non-violent offenses), including undocumented people, which is possibly why California now has more incarcerated than any other state in the nation.

The California prisoner hunger strike and work stoppage continues. The responses of the prisoners are causing the prisons to lose money. As of Monday July 15th more than 2,000 prisoners were still on strike, and more than 200 did not report to work or prison classes. The numbers are expected to go down, but the presence and pressure from the outside will only grow in solidarity with prisoners risking their lives for just and humane conditions.

On Saturday, near one of the side entrances of the prison we rallied and demonstrated our support. Corcoran State Prison is a super-maximum security facility. It has an abusive Security Housing Unit. As organizers addressed the demonstrators, I was taken back to the first time I flipped through the prisoner letters that La Gente Newsmagazine receives, many of which come from Corcoran SHU. I remember the poems and artwork that were attached to the letters. Each letter is marked with such caution; talented with the pen, these letters are stylistically exquisite. You can sense the heaviness of their experiences. They are such inspirational words that address their lives and their hopes and dreams. It means a lot to the prisoners for people on the outside to listen to their voices, to understand their positions within a larger framework of systematic abuse and scarce economic opportunities.

On our way back to Inglewood, Bilal Ali, community organizer, received a message saying that Corcoran prison officials were punishing prisoners suspected of being involved in organizing the demonstration. They confiscated their canteens, taking away their water and threatening some with longer solitary-confinment sentences. Prison officials are labeling the actions as mass disturbances despite the peacefulness of the prisoners’ protests.

This issue has brought out all the injustices of the criminal justice system once again. Over a week of protest now and los presos siguen luchando, demanding that they be heard.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!