The East LA Walkouts of 1968:“It was beautiful to be a Chicano that day”

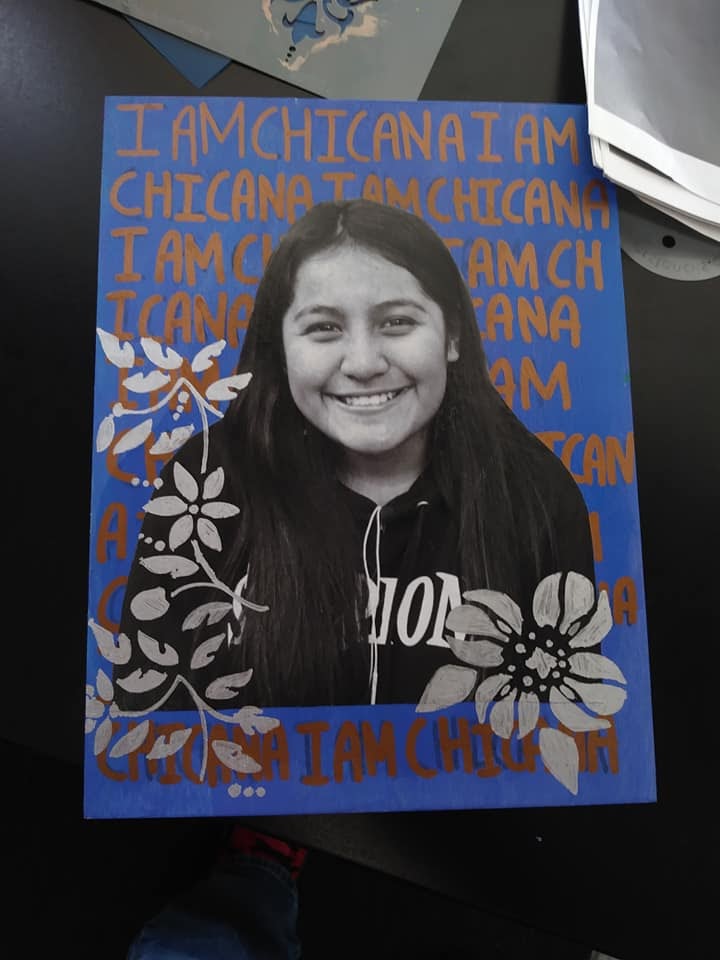

“I am Chicana” art piece and photograph by Melissa Torres

Fifty-three years ago, over 15,000 students from seven high schools in East Los Angeles walked out of their classrooms in protest against education inequality. These schools were underfunded and racist towards Mexican-American youth and other neglected minority groups. Some schools forbade their students from speaking Spanish in their classrooms, even going so far as to physically punish them if they did.

At the time, Mexican-American students reported a 60 percent high school dropout rate, and of those that graduated, most read at an 8th grade level. Classrooms were overcrowded, and the counselor to student ratio was 1:4000. Faculty and staff discouraged students from pursuing higher education and promoted a more vocational path.

In an interview with Lincoln Heights alumni and student walkout organizer, Paula Crisostomo, she recalls being told by one of her teachers, “We all know you’re never going to college. You and your girlfriends back there are going to be pregnant by the end of summer. Go and sit down. Don’t waste my time.”

Luckily for Paula and her peers, they were heavily influenced by their social studies teacher, Sal Castro, to challenge these stereotypes and demand a better education. Unlike other teachers, Castro listened to the students and held higher expectations of what they were capable of. He was committed to increasing high school graduation rates and college enrollment. Castro accomplished this by inviting students to the Mexican-American Youth Leadership Conference, a gathering where attendees received mentorship from Chicanx college students.

Through Castro, Paula and her classmates became aware of the systemic problems that were negatively impacting Latinx students. Castro took a group of students to Fairfax High School, which was “a gleaming, new school at the time” according to Paula. Fairfax, however, had a predominantly white student population at the time. The students learned that this well-resourced campus was in the same district that served their school. In turn, this made them realize the poor conditions and unequal education that the Eastside youth faced.

Additionally, Castro’s teachings encouraged students to embrace their heritage. As a social studies teacher, he incorporated Mexican-American history into his lessons. This exposure encouraged students to embrace their culture, and Castro used this to shape them into active leaders. This made Castro a prominent figure in the Chicano community and an instrumental contributor to the walkouts because he helped organize the demonstrations and amplified student voices. With the guidance of Castro, students took it upon themselves to bring change in their high schools by listing demands to present to the board. Initially, they created surveys to hear students’ complaints, needs, and wants. These surveys were then presented to the LA Unified School District board, but were disregarded.

Students from Lincoln Heights, Wilson, Roosevelt, Garfield, and Belmont high schools grew tired of being ignored. Paula recalls “I felt angrier and angrier and angrier.” Still, Castro insisted they try other ways to get their voices heard.

After six months of planning, high school students from all across East Los Angeles walked out on March 5, 1968. Castro stated that “as the bell rang, out they went, out into the streets. With their heads held high, with dignity. It was beautiful to be a Chicano that day.”

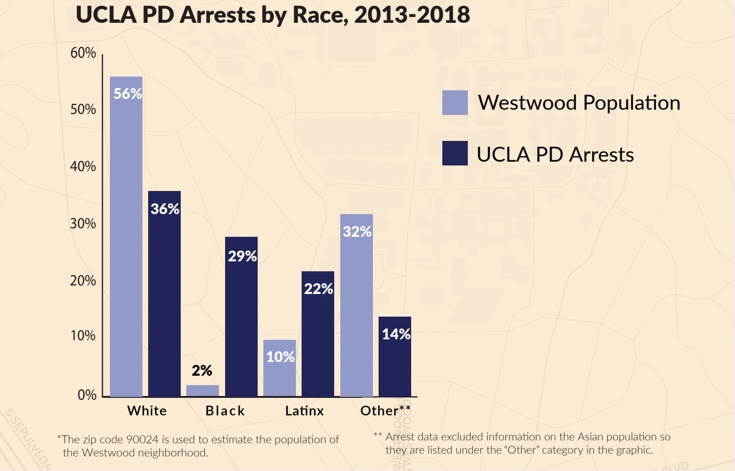

These peaceful demonstrations were violently disrupted by law enforcement. Students were brutalized and punished by police officers and sheriffs simply for wanting a better education. Two student beatings and multiple arrests were reported during the walkout at Roosevelt according to KCET.

On March 28, 1968, students presented their demands at the school board meeting. Some of these demands consisted of bilingual education, ethnic studies, and hiring more Mexican-American faculty and staff. Still, LAUSD denied these requests.

While a change was not achieved immediately, the walkouts of 1968 remained significant. These demonstrations were one of the largest acts of student civil disobedience in Los Angeles and catalyzed for the Chicano movement. The walkouts created a political and cultural awakening about the Mexican-American experience and influenced a civil rights era dedicated to improving their harsh realities. During this movement, advocates fought for Mexican-American representation and equal treatment in U.S. institutions like education.

However, it has been over 50 years since the first walkouts, yet academic disparities persist. As Castro concluded before his death, “the fight isn’t over.”

This previous year, Latinx students were the largest group to be admitted to the University of California, making up 36 percent of the incoming freshman class. Recently, it was revealed that UCLA also saw a 12.2 percent increase in Latinx applicants this year. These historical moments are challenging the idea that Latinx folks are not destined to graduate high school or pursue higher education. Still, this does not equate to more representation in higher education.

In an interview conducted by USA Today, Deborah Santiago, one of the co-founders of Excelencia in Education, an advocacy group focused on Latinx students states: “You can’t just enroll them if you’re not going to help them graduate.” College campuses fail to address retention rates that disproportionately affect Latinxs and other marginalized groups. Latinx students, the majority of whom are first-generation, struggle to survive in college.

Leslie Hurtado, a first-generation Latina student, also shares her troubling experience at Columbia College Chicago with USA Today. Like many campuses, the university prides itself on having a diverse student body, but when Hurtado got there, she was the only Latina in her class. This was Hurtado’s first experience of culture shock and being in a predominantly white space “made her feel small.” Additionally, college associated expenses placed a heavy financial burden on her family. Unable to afford the high tuition, Hurtado was left with no other choice but to drop out. The lack of cultural diversity excludes Latinx and other marginalized students and intimidates them by forcing them to navigate these unfamiliar spaces on their own.

Many colleges have yet to provide additional academic, emotional, and financial support to help Latinx and other marginalized groups graduate. Back in 2018, the degree attainment for Latinx students in California was 10 percent less than their white counterparts. Moreover, a research study conducted in 2016 by UNIDOS US reveals that Latinx students had a higher average cost of college (after subtracting their grants and expected family contribution) than white students. Although white students took out more loans, 1 in 3 Latinx students that also took out loans that same year did not attain their degree. The pattern remains; our institutions are unwilling to invest in our futures.

While some might argue that the walkouts of 1968 were unsuccessful, it is still worth honoring this important event because of its endless legacy that continues to impact Chicanx/Latinx students today. These demonstrations paved the way for more academic opportunities. We are still a long way from achieving equal education, and it is important to keep fighting and resisting. To learn more about the Walkouts of 1968, check out the documentary Taking Back the Schools, which includes real live footage and beautifully illustrates this movement.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!