Diversify Our Narrative: Social Activism in the Digital Age

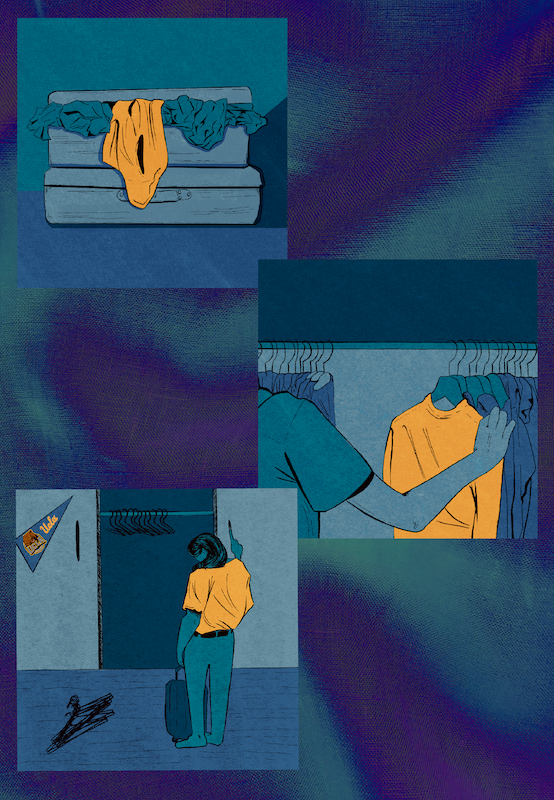

Illustration by Sofia Rizkkhalil

When I was in the tenth grade, my Honors English teacher assigned Maya Angelou’s I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings. It was the first time that a book written by a BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color) author was used in my instruction, and more to the point, the first time anti-racist literature was used educationally to further my understanding of the Black experience in America.

While some high schools incorporate BIPOC authors into their curricula and place the same emphasis on the educational value of their corresponding texts as those penned by white authors, the harsh reality is exposure to these narratives can often be limited for students before they get to college. The Diversify Our Narrative campaign hopes to rectify that.

Co-founded this past June by two Stanford rising sophomores, Katelin Zhou and Jasmine Nguyen, the DON campaign fights for the inclusion and integration of “anti-racist and diverse texts in English and Literature classes” within the United States. Galvanized by the nationwide protests that arose in response to recent waves of racial injustice, Zhou and Nguyen questioned where they learned about racial intolerance and the systems that are in place that perpetuate these inequities. They soon realized that it was not until they reached college that their education touched on these topics. From there, the idea for Diversify Our Narrative was born.

The DON campaign is student-led and hopes to target school boards across the nation by mobilizing organizers and facilitating the lobbying process by providing the blueprint to take action. Regardless of whether a student attends a public, charter, or private school, those looking to get involved will find everything they need to get started on the Diversify Our Narrative website. The site features various resources ranging from action guides that carefully array every crucial step in organizing district appeals, to their recommended reading list, and all necessary templates for a myriad of petitions.

Conducive to their chief objective, the first proposition that the group makes in their primary petition to diversify curricula mandates that “a minimum of at least one book in every English/Literature and Comprehension class be by a person of color AND about a person/people of color’s experience(s).” Not stopping there, the petition reinforces DON’s cognizance of the anti-Blackness rhetoric and sentiment within our nation and desire to address the ever-present racism through education by advocating for “at least one of the mandated books [to] be about the Black experience.”

In addition to the strategies the DON executive team employs to simplify petitioning school boards, a lot of their success in organizing can be traced to their social media presence. In just under three months, their Instagram page alone has reached over 108K followers. While Zhou feels that part of the reason they have gained such traction is due to the sharable nature of their calls to action and the accessible language used in the educational posts, she attributes a lot of their success to the “momentum created by all the Black activists.” Correspondingly, Nguyen notes that “now that there’s all this conversation, we can take this power and change our school systems thanks to the Black and Brown organizers that have paved the way for this to happen.”

When asked about the posts on the page, Zhou explained the aim of their graphics extends past simply trying to get people involved in DON’s mission; they try to “create any sort of educational content that relates to something in the education system… and to race.” From their debriefs on certain books to their posts about specified microaggressions, this practice is exemplified by the diverse topic sets featured on their account.

Now, as with any large social media presence, the group has also faced backlash in the comments section from students and adults not in favor of the proposed changes. Opponents often contend that the books read in classrooms should not be about the race of the author, rather the quality of the writing and that the “classics are classics for a reason.” Some even assert that the initiative is attacking white authors.

However, in response to those critics, Zhou wants them to know that DON is “not trying to eliminate authors because they’re white, we’re trying to expand the scope of what we’re reading in the classroom.” Failure to incorporate texts written by BIPOC into our education means that “we’re missing a fundamental component of our understanding of the world we live in,” Zhou elaborated.

“Failure to incorporate texts written by BIPOC into our education means that ‘we’re missing a fundamental component of our understanding of the world we live in.'”

Addressing the classics argument, DON’s Co-Director of Communications and Yale rising sophomore—Katherine Matsukawa—wants people to consider that “who defined them as classics in the first place has a lot to do with white normativity… we’ve been trained by the systems in place that white equals normal, but there are books that are equally good and insightful that offer a different perspective.” Ultimately, the team is incredibly intentional about the language they use to avoid misconceptions. Even so, to help dispel these errors, they often further clarify their position by interacting with followers on Instagram live, answering direct messages and producing more educational content.

With the campaign gaining so much traction, it is unsurprising that DON has already seen some of the fruits of its labor. This past July, organizers were able to get on the official board meeting agenda of the Manteca Unified School District. Moreover, there have been a “handful of districts speak at their board meetings during the general public comment section and a lot of them have hit 1,000 signatures” on their petitions, said Matsukawa. Nevertheless, the initiative is still well on its way to accomplishing its primary directive.

As the implementation of this initiative ultimately happens in the classroom, support from educators is pivotal. Fortunately, Zhou notes that “for the most part, a lot of the teachers the school districts have reached out to have been supportive,” even going so far as to sign the petitions themselves.

While DON has yet to get a school board to approve its proposed changes, its reach, solidified in such a short period, represents the importance of timing and intersectionality when it comes to racial issues. Sandy Nguyenphuoc, DON’s Director of Design and incoming UCSD freshman, was one of the people “inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement… it helped [her] see that [she] needed to step up and take action,” sparking her involvement with the campaign.

Beyond that, Diversify Our Narrative represents a victory for mobilization in the digital era. In an age where social media activism is quickly gaining momentum, ensuring the success of any given cause requires easing the burden for those looking to get involved. Getting people to take that initial action can be heavily dependent on steps like reducing the time constraint or creating a link tree for easy access.

For some, sharing an educational post might be the extent of their advocacy. Others might want to become further involved but are not necessarily equipped with the knowledge on how to go about doing so. That is where Diversify Our Narrative truly shines; it encourages activism on all levels and lays the roadmap to serve as a guide. Skarlette Castejon, Co-Director of Communications and UCLA rising sophomore, explained that “many students of color experience real life issues within the education system, but don’t know what measures to take to change them, and this campaign gives them a way to do that.”

Moving forward, Zhou stressed that organized efforts to combat racism through education bring us “just one step closer to having more empathy and understanding for different groups of people.”

Fortunately for me, my teachers in high school were always extremely cognizant of that. They knew that knowledge is not limited to a single source; they could give us John Steinbeck and F. Scott Fitzgerald while also exposing our minds to the works of Zora Neale Hurston and Isabel Allende. Learning from one text was never mutually exclusive to learning from another.

As a biracial student, I knew the world looked different than the one painted solely by the classics, but analyzing the work of BIPOC authors helped contextualize that reality. More importantly, it made me feel grounded in the realm of academia, where often so many students of color can be made to feel as if they are on the outside looking in. It was a bridge between my education and my ethnic background, one where I felt the pages of my narrative represented.

While there is an inherent power in that, there is also no denying the general benefits of being exposed to anti-racist and diverse texts early on in your education. It will indisputably focus the lens through which you view the world, make you more receptive to perspectives that differ from your own, and shed light on realities that you might have otherwise been oblivious to. We should all want a future where the way people think of racism has nothing to do with where they fall on a political spectrum, where a history of oppression is not something to be debated or simply acknowledged, but remedied. Although calling for the inclusion of these texts is still ways away from the finish line, it is a necessary step in the right direction.

If you are looking to get involved with Diversify Our Narrative, I encourage you to visit their website to learn more about how you can help change the literature curriculum in your district.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!