Mapping the Chino subaltern: An exploration of the phantasmal history of Eastern Asian diasporas across Latin America

Visual Credit: Tommy Correa

Across the history of Latin American societies, there are very few documentations and narratives in the (re)construction of hybrid identities that transpired during the Spanish colonial viceroy. One of these identities that are subjects of invisibility in various paradigms of Latin American culture and politics is eastern Asian diasporas.

One of the bearings that facilitated this phantasmal citizenship of Asians in Latin America has been overshadowed and undermined by mestizaje. Lourdes Martínez-Echazábal, a Latinx American Studies Scholar, underpins the history of mestizaje across Latin America:

“During the nineteenth century, mestizaje was a recurrent trope indissolubly linked to the search for lo americano (that which constitutes an authentic [Latinx] American identity in the face of European and/or Anglo-American values). Later, during the period of national consolidation and modernization (1920s-1960s), mestizaje underscored the affirmation of cultural identity as a constituted by ‘national character’ (lo cubano, lo mexicano, lo brasileño, etc)” (21).

Echazábal, citing scholar Françoise Lionett, likewise reckons with the articulations of mestizaje as a way of stagnating our understanding of interracial identities in Latin America, revealing that:

“[p]ostcolonial critics and artists have redeployed the paradigm of mestizaje as transculturations as the ‘fertile ground of our heterogenous and heteronomous identities as postcolonial subjects” (37).

This, of course, is extremely problematic as it leaves interracial identities – that is those beyond the binary of European and Indigenous descendants – to take on a marginalized identity that bears the weight of invisibility, as is the case with Eastern Asians across America Latina.

Scholars like Evelyn Hu-Dehart and Katheleen López have dedicated themselves to unveiling the subaltern history of the Asian diaspora in Latin America. Hu-Dehart and López trace this contact between cultures back to Spanish colonization. The Manila Galleon Trade, that is the Spanish colony in the Pacific, facilitated the contact from 1565 to 1815. Census, contracts, and official governmental documentations of Asian communities date back to the early 16th and 17th century. However, these recordings did not become significantly prominent until the 19th century, after Latin American countries began to seek independence from the Spanish. In the onset of nation-state formation, many east asians individuals translocated to Latin American countries due to labor opportunities.

Following this discussion, at a more large-scale migration, Japanese immigration was induced before the 19th century, many of which settled in areas like Guatemala, Mexico, and Peru. Hu-Dehart and López found that many of the early migrants varied from various occupations, most were predominantly agricultural laborers, and in the more narrow side of migrant numbers lied students, businessmen, sailors, teachers, and journalists.

At a more contemporary level, Latin America is no longer a site for cheap labor, instead, because of enforced neoliberal economies across Latin America countries, America Latina became subject to neo-enslavement. Today, Latin America covets for economic gain at the expense of impoverished latinx communities, in that maquiladoras, —sites of exploitations and cheap labor— have been feeding the pockets of corruptionist agendas disguised to be “modern” tactics to be apart of the global economic integration. Largely these maquiladoras are ventures of foreign capital investment that are coming from more industrialized nations like China, Japan, and Korea.

PERU

Another country that currently holds the second-largest Asian population is Peru. Japanese settlement began in 1898 when the coastal plantations attracted foreign contract laborers from Japan. This emigration, according to Ayumi Takenaka, was highly encouraged by the Japanese government. In fact, the Japanese government granted subsidies through institutions like the Social Affairs Bureau, the Ministry of Overseas Affairs, and the Emigration Center, and the Emigration Cooperative Societies, to those who wished to relocate to Peru. This agenda was pushed as a result of Japan’s overpopulation and economic benefits, which greatly increased the capital of diasporic families through foreign remittances.

One of the various acts of discrimination and exclusionary tactics in governmental, societal, and economic spheres was set in March 1917. The Anti-Asian Association, founded by a labor union in Lima, Peru, called into question (and denounced) the “yellow immigration” that the Peruvian government had put into effect in their newspaper “La hoja amarilla,” or “The Yellow Page”. One of the first measures implemented at a policy level was the annulation of contract migration in 1923. This was excused by the fact that many Japanese immigrants had escaped the plantations when in reality, demand for labor had downturned. Another decree was catapulted in 1936 which negated the re-entrance of Japanese immigrants to Peru, which stymied Japanese migration. Shortly after, in 1937, the Peruvian government denied citizenship to first generation Japanese-Peruvians. Staggerly, in 1932, “the 80 Percent Law” obliged enterprises for 80 percent of employees to be Peruvian (Takenaka 86-87).

MEXICO

One of the many countries in Latin America in which contact and translocation of Chinese diasporas exists is Mexico. The case of Mexico is particularly interesting as Chinese immigration did not begin to occur until the 17th century. However, this immigration did not become significantly staggering until the Chinese Exclusion Act decree by the United States in 1882.

This policy completely banned Chinese individuals from entering the country for a 10 year period. The Chinese Exclusion Act was a form of enforcing racial borders, in which concerns about maintaining anglo-american hegemony threatened the racial hierarchies. This growing discourse entrenched by racial othering was further developed by worker demands.

In which case, according to Latin American scholar Rocío Gomez, in 1899, the Qing empire (1644-1911) and Mexico signed “The Treaty of Amity, Commerce, and Navigation”, which facilitated migration of Chinese immigrants under governmental protection.

Chinese communities settled in northern Mexico. In fact, it was by 1923 when Chinese population numbers spiked, having 3,000 Chinese immigrants in the state of Sonora alone. Similarly, Gomez reports that in Mexicali, Baja California, many Chinese workers began to settle there as a result of cotton in 1902. Moreover, in their settlement across the years in the northern region, thanks to the growing economy, many Chinese immigrants settled to later prosper, which allowed them to set up businesses like restaurants and other enterprises. This however, was not well received by neighboring Mexican people as it created a catalyst for a growing racist campaign against Chinese immigrants.

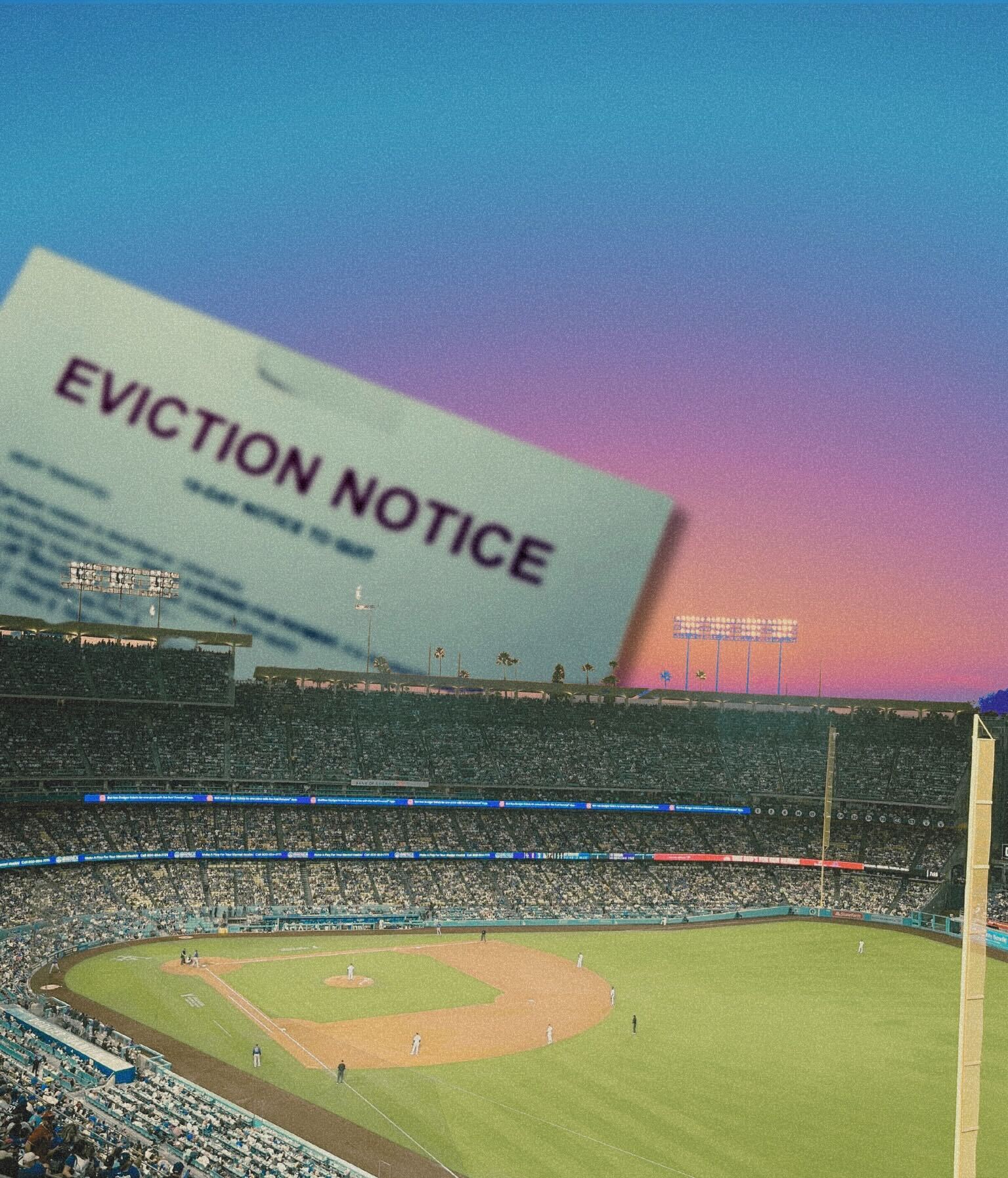

Following the growing anti-Chinese sentiment, the city of Torreón, Coahuila witnessed the worst massacre of Chinese immigrants. In 1911, Chinese communities were prosperous in the city, with a staggering population of 35,000 Chinese immigrants. As a result of economic prosperity, many Mexican individuals were discontent which motivated individuals like Jesús C. Flores to publicly denounce immigration and condemned the Chinese with their own financial struggles.

Amidst the revolutionary war, an act of mob violence ensued in 1911, which was led by Maderistas guerillera. This racially motivated strike against the Chinese community created a catastrophic and detrimental massacre to the city of Tórreon. In the historical accounts, it is recorded that as many as 300 Chinese immigrants (including women and children) were brutally murdered. Scholars like Chao Romero view this event as the “worst act of violence” against diasporic Chinese communities in the 20th century.

Cuba

Lastly, summing the history of Chinese immigration in Latin America, Cuba testifies to larger Asian immigration trends as early as the 19th century. In the late 1850s, Cuba was one of the largest sugar-producing countries worldwide. To note, a few years before this, in 1833, the abolishment of slavery had been effected in England, and thus Cuba being a colony of England, affected the demand for labor in sugar cane plantations. Cuba thus made itself a site for labor opportunities, which led many Chinese immigrants to settle in Cuba to work the sugarcane field.

According to Journalist Lisa Chiu, the first waves of migration began on June 3rd, 1857, when the first ships came, bringing 200 Chinese laborers under eight-year contracts. However, because the situations both within the ships and the labor conditions were severe – with many allegations of breach of contrats, in 1873, Chinese government appointed few investigators to Cuba to look into the staggering suicides rates by Chinese laborers. The investigation concluded by the banning of labor trade in 1874, once the last ship carried few Chinese passengers to Cuba.

At the height of Cuba-Chinese communities in the 1870s, there were more than 40,000 Chinese people in Cuba, according to census records. From these communities, Cuban-Chinese entrepreneurs led various enterprises in Havana, which led to the establishment of “El Barrio Chino”. El Barrio Chino summed 44 blocks, which was the largest in Latin America, and created ranging work opportunities for Cuban-Chinese individuals – many of these being restaurants, laundries, and shops.

In contemporary times, however, it is estimated that only 400 Chinese Cubans that were born from China reside in Cuba. Many of which live close to the Barrio Chino, while their grandchildren carry out their entrepreneurial shops.

Despite the long-standing historic intermingling between Asian and Latinx countries, these sites of contact have parallel hierarchical colonial discourses of contestations of race, identity, and territoriality. Alberto Fujimori’s identity, for instance, as the first Japanese-Peruvian president in Latin America, was a recurrent plot of exploration and interrogation in which media outlets exploited his identity as a site of public spectacle.

Most recently, during the spike of the global pandemic, we witnessed many vulnerable communities all around the world – Latinx-Asian collectives being amongst the many – who were constantly subjected to racist rhetoric and scapegoating tactics. This is the case for Brazil, who’s ranked to be the first country holding the largest Asian (specifically Japanese) population around Latin America. Public commentary shows exactly this rooted hate against Latinx-Asian, and Asian communities, with the son of the previous Brazilian President, Jair Bolsonaro, publicly denouncing “China’s governing Communist party for the coronavirus crisis sweeping the world.”

Precisely, the imaginaries of what is perceived as Latinidad are not resistant to identities divergent from mestizaje, which is why it is necessary to reconstruct how Latinidad is imagined, through the exploration and the interrogation of Latinx histories. Homogenizing terms and discussions, such as those that took place during the global pandemic, or even in the trivialization of a codified Asian (uniformed) identity across Latin America, must be continuously challenged. Historically, we see that this hegemonic discourse dating to colonial matrixes of homogenization seek to frame heterogeneous identities, which in turn, produces racial divisions that fixes the Asian as foreign and not as what it is – a community that not only extends and transcends the limitations of Latinx identity but a community that contributed, forged, and resisted, the face of an oppressive colonial gradient.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!