Out of the Shadows and Into the Light

In Southern California, gardeners working on private lawns throughout the day have become a common sight. As most people drive around Beverly Hills, there are no second glances, and are no second thoughts about the many women of color waiting for the bus. However, a local artist has found a way to bring the issue of overworked and underpaid gardeners and housekeepers in a creative way.

Ramiro Gomez, 25-years old, places cardboard cutouts of laborers in public places all over Beverly Hills as a way to attract attention to the issue.“[I want to] reach an audience that has been desensitized in so many ways,” said Ramiro when describing the reasoning behind his work. He needed to find a way to remind everyone about the men and women behind the labor, to remind them the importance of the labor issue among immigrants. In the apartment he shares with his partner in West Hollywood, Ramiro has a room devoted to his projects. There he paints life-size cardboard cutouts of faceless laborers and then places around Beverly Hills in positions that display them as if they are hard at work. “[I am] not trying to imitate real life. I am trying to represent real life.”Born in San Bernardino to a working class family, Ramiro was raised by his grandmother. Because both his parents had to work, she was his primary caretaker and spent summers with him. After attending Riverside Community College, Ramiro moved to attend CalArts in 2006. However, while attending the art school he realized he did not belong. His transitional period came at a time of loss with the death of his grandmother, prompting him to find a new sense of direction in life. As a way to connect his grandmother and the past that was lost, Ramiro took a position as a male nanny for twins in Beverly Hills in August 2009. From his experience as a nanny, it allowed Ramiro to connect with the present, and deal with his grandmother’s death.

Ramiro’s work came as a result of this organic, therapeutic process of trying to identify with the home he knew to the life he found himself living. While the twins took naps, Ramiro began drawing on magazine pages at first without an obvious reflection. The magazines he doodled sold the idea of a beautiful house. His drawings became a sort of diary, a diary reflecting his experience and unhappiness at the job. In the magazines he felt ignored because they pictured a perfect house without the reality he saw every day, the reality that behind those pictures were people who kept the home looking nice every day. His drawings began by melting the paint, for example, in a picture depicting a state of the art kitchen and an empty stroller in the middle. Ramiro’s artwork soon developed into actual drawings of a person in the environment the magazine glamorized. He was dealing with the truth that had been rejected from their ideology, he said. It was a way to understand that he and others like him were not invisible.

After some time, Ramiro realized his art belonged to a bigger picture, it was more than him trying to identify with his environment, but something bigger. Soon he set up his own blog called Happy Hills, and actively sought out other people who talked about the issues his drawings projected. Ramiro became motivated to meet people who brought attention to the topic of immigrants, such as director Chris Weitz, or events at UCLA and UC Santa Barbara. The young artist places much importance on the new age of technology as a way to get his message across, such as Twitter and viral videos that has exposed him to many others.

Today, Ramiro places life size cardboard cutouts of gardeners around LA in order to get people to notice those who have become a common background in the big homes of West Los Angeles. He hopes that when people see his cut outs while their driving, they will see the real person and think about how “our choices benefit them.” Ramiro believes, unfortunately, taking advantage of those who don’t have a voice is “the way it has always been.” It is a form of racism so ingrained without an full historical understanding of it. His cardboard cutouts are criticisms of how gardeners and day workers are treated, and a way to show his anger without violence, to draw attention without yelling.

With the upcoming presidential election, Ramiro is looking for change, and is strategically placing his cardboard cutouts to spark attention to the issue and create conversation. On May 10th, when George Clooney held a fundraiser for President Obama, Ramiro placed new cutouts on a street he knew the President would drive through. He was angry, Ramiro explained about what prompted his actions. He hoped to start a conversation about how many people were willing to pay $40,000 to attend the fundraiser, but refused to pay a fair salary to those cleaning their homes and working in their gardens every day. Although his actions brought him attention and contacts from many other civil rights groups in San Francisco and Arizona, his cardboard cutouts were removed from the location.

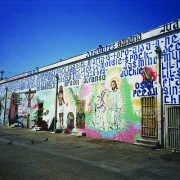

“I would love to do a permanent mural in Beverly Hills,” said Ramiro when talking about his future, “there is nothing more pressing to me than achieving permanence there.” He believes people need representation there, in the place that is a different world all on its own. However, all in good time, as Ramiro sees his cutouts as non-damaging murals talking about issues while explaining the community. In the mean time, he is working on his art and creating projects for a show at a gallery in Culver City. Ramiro is certain he is already placed on a “watch list,” but he will continue connecting with others through his work by not standing and waiting for change.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!