Not Just a Man’s Job

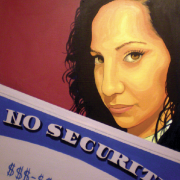

![]() Every day Maria Elena Garcia enters the Community Job Center in downtown Los Angeles which is filled with male day laborers. She waits for a job as she watches another man get picked. The sign outside the center that reads “Hire Day Laborers and Household Workers” makes Garcia reflect on the journey that brought her here four years ago from Jalisco, Mexico.

Every day Maria Elena Garcia enters the Community Job Center in downtown Los Angeles which is filled with male day laborers. She waits for a job as she watches another man get picked. The sign outside the center that reads “Hire Day Laborers and Household Workers” makes Garcia reflect on the journey that brought her here four years ago from Jalisco, Mexico.

Seeing no opportunity for work and desiring to provide her son with a thriving future, Garcia parted from her old life and set out on a solitary trip to the North.

Upon her arrival, she found assimilation into the host society extremely difficult. Missing her son and unable to find a stable job, she quickly slipped into a debilitating state of depression, which was also triggered by a stagnant cycle of searching but not finding. “I hadn’t been here even one month when I grew tired of this country’s persistent rejection. I couldn’t stand the loneliness, so I decided to bring my son over here.”

Upon her arrival, she found assimilation into the host society extremely difficult. Missing her son and unable to find a stable job, she quickly slipped into a debilitating state of depression, which was also triggered by a stagnant cycle of searching but not finding. “I hadn’t been here even one month when I grew tired of this country’s persistent rejection. I couldn’t stand the loneliness, so I decided to bring my son over here.”

With her son in the states, Garcia had a even greater need to find stable employment. Although she had a steady job for some time and was providing for her son and her family, she unexpectedly got laid off. As a result, she was forced to move out of the room she was renting and into the living room of an apartment.

When asked to describe a regular day in her life she begins, “I wake up, thank God for another day, I feed my son, send him to school, and walk to the center. I spend most of my day there.” At the downtown center she spends hours waiting for a job. If she is offered one, she accepts it. If she does not, she begins making and distributing business cards with the domestic services she offers.

As one of the few women who attend this center, Garcia seems almost desensitized to being the only female presence there. Upon being asked if she feels out of place, Garcia responds, “No, the moment I step here, I forget that I am a woman.” More than just putting aside her identity as a woman and assuming the identity of a day laborer, Garcia also becomes male day laborers’ competition for work. When asked if she would perform a man’s job, without hesitating she responds, “Yes.”

As for the differences between jornalero men and women, Garcia is very clear in emphasizing her belief that women have an overall advantage over men. “We are charismatic; we can adapt better to situations, and can perform a greater array of domestic jobs,” she says.

Despite her certainty in the female advantage, she also expresses reservations about potential disadvantages. The greatest of these is the position of subordination in which women are often put. Because this is a male-dominated environment, women mostly interact with men. Often, a woman is offered a job by a male, meets him at their agreed location, and quickly discovers that what she is being offered is in fact a different and morally degrading domestic job.

Another common situation is when housekeepers become victims of abuse by the male of the household. Their fear of deportation combined with their need for money forces many of these women to allow this abuse to continue for long periods of time. Whether it is verbal or physical abuse, it ultimately transcends into psychological abuse, driving them into a state of constant fear, anxiety, and disgust.

It is experiences like these that shake the resolute faith of jornalero women like Maria Elena. “Things are really dangerous here now. Almost like Mexico, but without your family to support and look out for you,” she says.

In regards to where she sees herself in five years she says, “In Mexico, in my home. I’m tired of being alone here. I want to be with my family.”

If given the opportunity to do this again, she “would think twice now that (she) has seen the discrimination, abuse, and impossibility of assimilation.”

Despite her desire to return to Mexico, Maria Elena embraces life every day. She realizes that she has a responsibility here: “These things scare me, but they do not stop me from taking any jobs. I have a responsibility to my son.” Indeed, it is God, her son, her family, and her own positivity which keeps her motivated. “The dissolution I feel after getting a door slammed in my face is hard. But, the dissolution I feel after realizing that I am an invisible burden to this society is unbearable.”

With saddened eyes that reveal her sorrow that illuminate her face, Maria continues, “But even if I have to do it with tears in my eyes, I force myself to stay positive and be thankful for the things I have and the things I don’t.”

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!