No soy de aqui, ni soy de alla: Temporary Protected Status

Illustration by Maria Renteria.

The recent passing of the California Dream Act is a victory to many undocumented students giving financial aid to all students. Despite this victory, there are students outside of these two categories.

Liliana Leon, a second-year comparative literature student, has lived in the US since she was five months old. She came with her mother through political asylum that was granted to her when she fled El Salvador due to persecution.

She had the typical Latino American life growing up with her two younger siblings who are both citizens. Liliana was not fully aware that she wasn’t a citizen in the country she has called home.

In 2001, her mother was already trying to get Liliana out of asylum by applying for residency through her grandfather. In 2006, she realized that she was not a citizen. Her mother told her that their political asylum was going to be negated because the government would decide that the threat to her mother was not imminent. They would become undocumented if they didn’t find another alternative.

Immediately Liliana and her mother applied for Temporary Protected Status to remain in this country. Her mother believed that having Temporary Protected Status would be much better than being undocumented, because her daughter would not have to struggle. However, Liliana never foresaw the problems this new knowledge or her new legal status would bring her.

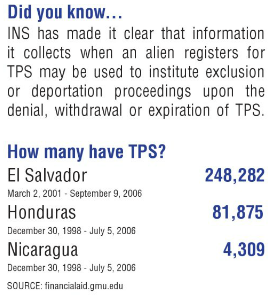

Temporary Protected Status, commonly known as TPS, was created under the Immigration Act of 1990. TPS allows the Secretary of Homeland Security to grant temporary immigration status to residents from selected countries that face environmental disasters, armed conflicts or extreme temporary conditions. Currently, these countries include El Salvador, Haiti, Honduras, Nicaragua, Somalia, Sudan, and South Sudan.

Individuals with TPS are in the country legally and do not have to fear deportation by the government. However, they are not a legal resident or citizen of the US and have no opportunity through TPS to obtain residency or citizenship.

“From the stories I’ve heard it’s difficult to be in TPS because there is not a lot of information on it. [Other undocumented students] assume TPS individuals have more rights or privileges and it creates divisions,” said Professor Leisy Abrego of the UCLA César E. Chavez Department of Chicana/o studies.

They are allowed to work and pay taxes but do not receive any government aid, including financial aid to attend a university. Individuals on TPS have to continuously make sure their paper work is in order. They renew their application every nine to twelve months paying $515 to get a piece of paper stating they have Employment Authorization.

Lawyers have not been able to help Liliana and her mother pursue residency under TPS. They have now gone through two different lawyers who have taken their payment without furthering their application through the immigration system.

Almost everyday Liliana faces trouble due to the complexity of her status. She has to explain countless times what it means to have TPS.

This becomes difficult when dealing with office workers from the Registrar’s Office and the

Financial Aid Office have never heard of TPS. This was especially true when applying to UCLA, paying for UCLA and applying for scholarships. Liliana has no way to label her situation. On official documents, there is no box to check for TPS. On her UCLA student file, it says residency pending. Several times she has had to argue with the Financial Aid office to not charge her out-of-state fees.

When the California Dream Act passed, Liliana was hopeful that she would be able to receive financial aid previously unavailable to undocumented students. However, these scholarships, including one from UCLA Academic Advancement Program (AAP), are only available for students with AB 540 status.

When I interviewed AAP assistant director Chante Henderson, she stated that AAP will award scholarships to an estimated 70 students, each with a value of $2,500. However, since Liliana’s UCLA status says residency pending, she does not meet the qualifications of the scholarship.

Liliana will still apply for the scholarship, but there is no guarantee she will be given one.

“The Financial Aid Office said they had to be AB 540. It had to be a quick turnaround to give the scholarships but in the future, when there is more time to organize, it will hopefully change in the future for other statuses,” Henderson said.

The director of the UCLA Financial Aid Office Ronald Johnson echoed the same sentiments when asked about students with TPS and financial aid.

“The financial aid office is only designating scholarships for AB-540 students. If she has AB-540 on an application, she should be able to apply. We are trying to help students who are undocumented. Since I am not an immigration specialist, I am not sure how financial aid will work. There is a really fine line and she may be eligible,” Johnson said.

Henderson and Johnson hope that the financial aid process will become open to more statuses in the future. Despite the passing of the California Dream Act, both individuals were not previously aware of TPS and how it affects obtaining financial aid.

Recently, the Registrar’s Office has asked Liliana to re-clarify her residency status for winter quarter. Under TPS regulation, she can claim AB 540 status. An action that Liliana is considering in order to avoid the confusion of her residency as well as make it easier to apply for scholarships.

“I have to show my work authorization card to co-workers so they can see I have a legitimate status and every time I apply for a scholarship or other jobs the question about my legal status pops up and every time I become self-conscious of how different I am.”

When I asked associate registrar Cathy Lindstrom via email about statistics regarding UCLA students with TPS, she responded that UCLA does not keep records of students with this status. Their residence deputies have not dealt with students of this status for the last year.

When I interviewed Liliana, she expressed a common sentiment many Latinos feel,

“No soy de aqui, ni soy de alla,” as composer Facundo Cabral once said.

“I feel I am being labeled as an outsider. Not just because I was born in another country and have a different cultural experience from everyone else, but I am physically being labeled and targeted as different,” said Liliana.

Her citizenship may belong to El Salvador, but in her own opinion she has no connection other than her mother to her native country. She has lived in the US her whole life, but she cannot claim American citizenship.

If for some reason their TPS is not renewed they will become undocumented and easily deported because ICE has records of them.

“I’ve heard of many cases where individuals with TPS who are one day late with their renewal application are immediately deported because the government has all their information,” said Professor Abrego.

For Liliana, it leaves her struggling to figure out how to pay for school without any aid, having to commute and work long hours, as well as having to justify herself to people who do not understand.

“My situation is so obscure I feel a bit marginalized because people label things. Either you are here legally or you are not. They don’t see the gray area that immigration system has created. They don’t understand that they can’t send you back because you feel political persecution but at the same time they don’t want you, so they put you in a marginalized place where you don’t have a lot of political representation.”

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!